The Truth About Countertenors

By Bruce Lamott

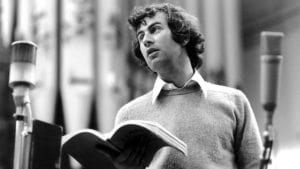

Alfred Deller

The story goes that upon hearing the voice of the late countertenor Sir Alfred Deller in a recital in the 1950s, one dowager whispered to her companion, “Now I know why he wears the beard. It’s to cover up the scar from the operation!” Not only did this lady need a refresher course in male anatomy, she also revealed a frequent misunderstanding of the difference between a countertenor and a castrato. While the latter were surgically altered in boyhood to prevent the onset of puberty–a barbaric practice simultaneously employed and condemned by the Catholic Church in the 17th and 18th centuries, the countertenor voice is a fully intact adult male alto or soprano singing with what, unfortunately, is called “falsetto.” There’s nothing false about it.

Every adult male confident of his masculinity is able to produce this sound (usually alone in the shower or the car), as it consists simply of vibrating the inner edge of the vocal cords rather than the whole vocal cord. Vibrating these ligaments alone produces a higher pitch and flutelike tone quality which requires compa

Every adult male confident of his masculinity is able to produce this sound (usually alone in the shower or the car), as it consists simply of vibrating the inner edge of the vocal cords rather than the whole vocal cord. Vibrating these ligaments alone produces a higher pitch and flutelike tone quality which requires compa ratively little effort. Native Hawaiian singers, American cowboys, and Alpine yodelers all employ a rapid alternation of full-cord singing, also called “chest voice,” with “modal” singing, the preferred and nonjudgmental term for “falsetto.” The success of Frankie Valli, the Beach Boys, and the Doobie Brothers as well as classical ensembles such as Chanticleer and Clerestory all depend on these modal countertenors to enhance their harmonies and expand their potential range.

ratively little effort. Native Hawaiian singers, American cowboys, and Alpine yodelers all employ a rapid alternation of full-cord singing, also called “chest voice,” with “modal” singing, the preferred and nonjudgmental term for “falsetto.” The success of Frankie Valli, the Beach Boys, and the Doobie Brothers as well as classical ensembles such as Chanticleer and Clerestory all depend on these modal countertenors to enhance their harmonies and expand their potential range.

While countertenors have been used for alto parts in all-male church choirs since at least the seventeenth century, the solo countertenor is a relatively new arrival in modern performances of opera and oratorio. Chorally-trained English countertenors sang in a rather hooty, one-vowel-fits-all tone quality more suitable for the austerity of Renaissance sacred music than the heroic display required of Baroque dramatic roles. Operatic countertenors today are cultivated to produce a brighter focused sound, with technical agility and strength necessary to be heard over an orchestra in a large hall.

James Bowman

Only in the last decades of the past century have voice teachers, conservatories, and operatic training programs accepted the solo countertenor voice as a legitimate Fach (vocal category) worthy of technical development. Not until 1982 did a countertenor (James Bowman) sing on the mainstage of the San Francisco Opera. And in 1991 the late Brian Asawa was the first countertenor selected for its Merola Opera training program, which in his memory recently created a foundation for the specific development of countertenors.

Italian castrato Carlo Scalzi by Charles Joseph Flipart, after 1738.

They say that hell hath no fury like a mezzo-soprano hearing a countertenor sing a role traditionally assigned to her. The incursion of countertenors into the alto solos in Handel’s Messiah in the 1970s established a beachhead from which they have proliferated today into the entire dramatic repertoire of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Because of the affinity for high voices by audiences in the gender-bending Baroque period, impresarios–both then and now–mix and match genders according to their vocal ranges and box-office appeal, not necessarily according to the sex of their role.

Hear renowned U.K. countertenor Iestyn Davies perform with guest conductor Jonathan Cohen and PBO in Operatic Heroes March 1-5 throughout the Bay Area. Get tickets here.

Here’s Iestyn Davies performing Handel’s “O Lord, whose mercies numberless”