Handel’s Radamisto

April 20–24, 2022

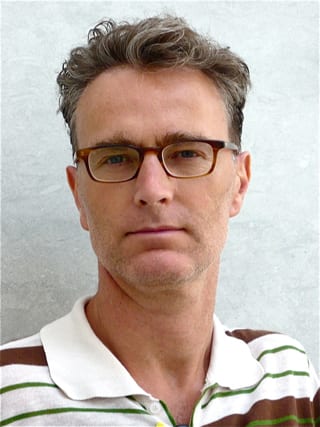

We honor Handel’s intended ‘wow factor’ of Radamisto with a new staging by Christophe Gayral, a familiar name in some of Europe’s most prestigious opera houses, giving us a fitting close to our 21/22 season.

HANDEL Radamisto (1728 version)

Richard Egarr, conductor

Iestyn Davies, countertenor (Radamisto–Senesino)

Liv Redpath, soprano (Zenobia–Bordoni)

Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone (Tiridate–Boschi)

Ellie Laugharne, soprano (Polissena–Cuzzoni)

Morgan Pearse, baritone (Farasmane)

Wallis Giunta, mezzo-soprano (Tigrane)

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra

Christophe Gayral, stage director

George Souglides, set and costume designer

Peter van Praet, lighting designer

”Relevant and effective dramaturgy, constant beauty, excellent direction of actors...first-rate work of Christophe Gayral and his team."

Opera Magazine

About Handel’s Radamisto

London’s West End is nowadays all about blockbuster musicals by a few household names, and in many ways that’s nothing new. Back in the 1700s it was dominated by none other than George Frideric Handel, the preeminent musical impresario of his day, notching up 50 operas, and always adapting his music and casting to ensure popular appeal.

Radamisto was a hit upon its 1720 premiere, and went on to even greater success in a 1728 rewrite, which starred Italian castrato Senesino, rumored to be paid the huge sum of £2,000 for the engagement, over $300,000 in today’s money!

As an ‘opera seria,’ Handel focused on giving famed virtuoso singers opportunities to shine via complex showy arias, and for these performances we haven’t skimped on those virtuosos, with star countertenor Iestyn Davies (former star of Farinelli on Broadway), joining us alongside a cast of truly exquisite voices.

We honor Handel’s intended ‘wow factor’ of Radamisto with a new staging by Christophe Gayral, a familiar name in some of Europe’s most prestigious opera houses, giving us a fitting close to our 21/22 season.

The Music

HANDEL Radamisto (1728 version)

Program Notes

For over two decades, Handel got on fine writing ‘opera seria’ for the King’s Theater—staged stories in which the Italian narrative was moved along by snippets of speech-song known as ‘recitative’, itself alternating with anguished soliloquies in which characters would reflect on their conflicted emotional states. The latter took the form of ‘da capo arias’—songs in three parts, with the opening music repeated after a contrasting middle section.

In a mode of storytelling almost entirely dependent on singing, Handel had the edge. Not only did his music plumb far greater emotional and psychological depths than that of his competitors, he was also able to tailor it to the specific strengths of the star Italian singers who pulled in the crowds. But those singers, and the impresarios who controlled the industry, were subject to fierce commercial rivalries and were often lured to rival companies for big bucks. A composer who could stay ahead of that particular game or even adapt to it—like Handel could—was worth his weight in gold.

Composers, however, were not immune from the variables of a London theater district powered by these rivalries. In 1719, a new company was established under the name the Royal Academy of Music. It wanted Handel as its chief composer and head of its orchestra, and soon secured him in both roles. The Royal Academy wasn’t averse to stoking rivalries even among its own house composers, who included Attilio Ariosto and Giovanni Bononcini. Handel surely knew that and accepted it as part of the rough and tumble of the West End. He knew how the game worked, and would prove as much in the first piece he wrote for the Royal Academy—Radamisto.

Handel was on familiar territory for this new opera—literally, as the Royal Academy had taken up residence in the King’s Theater where the composer had worked on and off for the previous decade. On 27 April 1720, Radamisto was first performed, in the presence of King George I and his son the Prince of Wales (the future George II).

For this particular adventure, they and the rest of the audience were taken to Armenia, around half way through the first century, where the tyrant King Tiridate wages war on the people of Thrace. The Thracians are led by King Farasmane and his son Radamisto. Tiridate also has designs on Radamisto’s wife Zenobia. Eventually a rebellion confounds Tiridate, who sees the error of his ways. Justice prevails and general rejoicing ensues.

The plot—a story from Tacitus’s Annals of Ancient Rome filtered through plays by Domenico Lallo and Georges de Scudéry and distilled into a libretto attributed to Nicola Francesco Haym—was not chosen by accident. As the late conductor Christopher Hogwood observed, Handel tended to favor stories in which the virtues of stability, hierarchy and orderly succession were underlined.

Those preferences did the composer no harm at the Royal Academy of Music, which was patronized by his own Hanoverian friends who doubled as the Kings of England and was bankrolled by a cabal of aristocrats. The composer dedicated the opera to King George I, thanking the monarch for his encouragement ‘not so much as it is the Judgment of Great Monarch, as of one of a most refined Taste in Art.’ Handel knew how to play a King.

When Radamisto proved a hit, it must have seemed like there was no pressing need to stray from the winning formula; all but one of the Royal Academy operas that followed would be dynastic epics like this one. It helped that Radamisto was lavishly produced and fairly well cast. In the first instance that cast was led by the Italian soprano Margherita Durastanti, known to Handel from his days in Italy. Durastanti wasn’t a household name but would probably have proved a draw by dint of her Italian nationality (society figures in London really liked their Italian music, literature, painting—and visitors).

Still, in its second season the Royal Academy set its sights higher. Subsequent to the first run of Radamisto in April 1720, the company signed the castrato Francesco Bernardi, known to the public as ‘Senesino’ (he was reportedly paid £2000 per year, around $300,000 in today’s money). A revival of Radamisto was scheduled for December of 1720 with Senesino in the title role—a singer with a different vocal range to that of the soprano Durastanti, for whom the role was written.

In fact, at least three of the opera’s roles changed voice-type for the December 1720 revival. Durastanti, a soprano, now took on the role of Zenobia, originally written for a lower-voiced mezzo-soprano. The role of Tiridate slid down from tenor to that of a bass, to accommodate the new singer Giuseppe Boschi. Handel scrapped the ballets that had closed each act, inserted a novel vocal quartet into Act III (‘o ceder, o perir!’) and deleted eight arias in total while adding ten more (mostly for Senesino).

For the revival of 1728—the model for today’s performance—the singer Faustina Bordoni arrived in London to snatch the part of Zenobia off Durastanti, thus taking it back down to the range of a mezzo-soprano. Meanwhile, Bordoni’s great rival Francesca Cuzzoni sang the part of Polissena (one role that stayed a soprano the whole time). The character of Fraarte, Tiridate’s brother, was jettisoned altogether.

Handel didn’t simply transpose his music for these new singers, or crowbar it into new shapes to fit their vocal preferences. On the contrary: he saw such cast changes as opportunities for improvement and reinvention. Every fine voice fascinated Handel, and he reacted to its individual capabilities acutely—re-writing music accordingly, yes, but always to further and advance the drama rather more than to indulge the singer (even as that singer’s characteristics were taken fully into account).

This handed a commercial advantage to whichever company Handel found himself writing for. But it also proved a potent musical tool. Handel mined extra layers of psychological and dramatic depth using a combination of his mind’s ear and his knowledge of the particular artistry of the singers he knew. Always in a Handel aria, there are subliminal meanings or byways into new forms of expression—whether in the voice or in the accompanying instruments. The voice in question was often the inspiration, which gives the music a naturalness that supercharges its dramatic effect.

Handel’s colleague, the flute player and composer Johann Joachim Quantz, described Senesino’s voice as ‘powerful, clear, equal and sweet’, and ‘with a perfect intonation and an excellent shake [trill].’ The castrato, according to Quantz, ‘sang allegros with great fire, and marked rapid divisions, from the chest, in an articulate and pleasing manner.’ Of Bordoni, he wrote of a vocal execution ‘articulate and brilliant,’ drawing attention to her fine articulation, and describing her as a vocalist who ‘sang adagios with great passion and expression.’

Those words were written, in fact, to the critic and contemporary of Handel Charles Burney, who concluded on seeing Radamisto in 1720 that ‘the composition of this opera is more solid, ingenious and full of fire than any drama which Handel had yet produced in this country.’ It was the most fully-scored of any of Handel’s stage works thus far, including parts for two horns, which accompany the bravura aria for the tyrant Tiridate, ‘Alzo al volo’.

The sort of sadistic threats levied in that aria were a standard feature of baroque opera, which reached for stories from ancient history precisely because they pit lust and violence against heroism and virtue; the allegorical implications were clear. Handel always sought more subtlety, as if to reflect on the nuances that characterize every human being; the predicament of those for whom heroism is more a matter of inner resolve or self-sacrifice.

We hear (and see) this personified in Tiridate’s unfortunate wife Polissena, who has the opera’s first word in the form of the cavatina ‘Sommi Dei’—a reminder, as a betrayed wife prays to the gods for guidance, that a domestic marital breakdown lies at the core of this opera of grand political machinations. This first piece of vocal music establishes a tension bordering on tragedy that propels the opera towards its conclusion. The character who delivers it appears to be the one human we meet willing to ask the most salient question: where, ultimately, will anger and greed of men lead?

Polissena channels her own frustrations into meaningful change, but not before she has harnessed them. In the furious aria ‘Barbarò, partirò’, she takes ownership of the jagged strings that lay underneath her opening prayer as she rails against her husband’s treachery and threatens to see him punished for it (faithful and wise, it is she who will eventually turn him onto the path of righteousness). Polissena also wraps up Act I with the hopeful ‘Dopo l’orride procelle’, dreaming of happier times with an upward-pining orchestra.

We first meet the character of Radamisto in the court of Tiridate, where he has travelled to try to appease the enemy King and secure the release of his father. The aria ‘Cara sposa’ was described by Burney as ‘elegantly simple’—a disarming expression of anguish whose conscious dramatic inertia demands a certain purity of expression. In the following act the character sings the darker and more mobile ‘Ombre cara di mia sposa’ assuming his lover Zenobia dead (she has in fact been rescued from the river into which she was flung). Burney considered this aria one of the best in all Handel, admiring the pained chromaticism in the accompanying strings that contextualizes a deceptively simple melody.

For Zenobia, Handel writes particularly evocative music. She sings the multi-layered ‘Son contenta di moire’ in Act I, movingly resolute in the face of death as she negotiates an aria whose considerable agility might paint a picture of Bordoni’s strengths as a singer. In the following act Zenobia has the theatrically fascinating ‘Empio, perverso cor!’ in which she alternately admonishes Tiridate with vehemence and sends concealed messages of affection to her disguised husband. When she and Radamisto must part in Act III, Zebobia’s desperate ‘Deggio dunque, oh Dio, lasciarti’, with its obbligato cello, rubs up against his doleful ‘Qual nave smarrita’. Their tripping reunification duet ‘Non ho più affanni’ prefaces the unusual, extended final chorus ‘Un di più felice’ which appears almost like a concerto grosso with voices in its ritornello verse structure.

So, all ends in rejoicing. Alas, there was no such triumph for the Royal Academy, which folded in 1728 shortly after the revival of the very Handel opera with which it had launched. Tastes had moved on; across town, John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, with music and story a world away from Radamisto, was packing in the crowds. The financial backers behind the Academy pulled the plug. Ever tenacious, Handel immediately set up his own replacement: the New Royal Academy. This German-born Londoner wasn’t done with Italian opera.

Rival Queens: Bordoni v Cuzzoni

The 1728 revival of Radamisto was one occasion on which Faustina Bordoni and Francesca Cuzzoni shared a stage. These days, the two Italian singers are known for a rivalry bordering on the explosive. Plenty of albums from contemporary female singers have taken this rivalry as their theme, extending the aura and mystery around an irresistible tale of two squabbling divas.

In fact, Bordoni and Cuzzoni knew each other long before they arrived in London from Italy, and had shared a stage several times before. The label ‘Rival Queens’ was invented by the London press, who lapped up the story and stoked the idea of a confrontation between the two women for its own advantage. Naturally, the opera companies saw the benefits too.

In London, the two women appeared together for the first time in a 1726 performance of Handel’s opera Alessandro. The flashpoint came a year later, when the two were both in the cast of Astianatte—an opera by Handel’s Royal Academy colleague Giovanni Bononcini. At the show on 6 June 1727, it is said that a fight broke out between the two singers on stage, each pulling at the other’s wig. That fit the narrative of two women said to be so egotistical and demanding that they struck fear into the composers who wrote for them.

These days, musicologists and historians question that version of events (it certainly seems unlikely that Handel, a big character in every sense, would have allowed himself to be compromised by a singer). It is now believed that it was the audience fighting on the night in question, not the singers. So partisan were the supporters of Cuzzoni and Bordoni that they themselves had initiated the riot of 6 June 1727, referred to by the satirist John Arbuthnot as ‘a most horrid and bloody battle.’ There can’t have been too much harm done between the women themselves, as they were back on stage together for Radamisto a year later.

Programme notes by Andrew Mellor © 2022