Our new seasons starts off this week, with a concert that’s a real treat for lovers of Handel. It features some of his finest instrumental music, plus overtures and stand-out operatic arias, in the company of our Music Director Richard Egarr and very special guest, countertenor Tim Mead.

Ahead of the concerts starting though we took a little time to delve into the deepest recesses of the classical internet to find out a little more about the man behind the music. It turns out that it’s not just his music that is larger than life. Here are 8 things we uncovered which you (maybe) didn’t know…

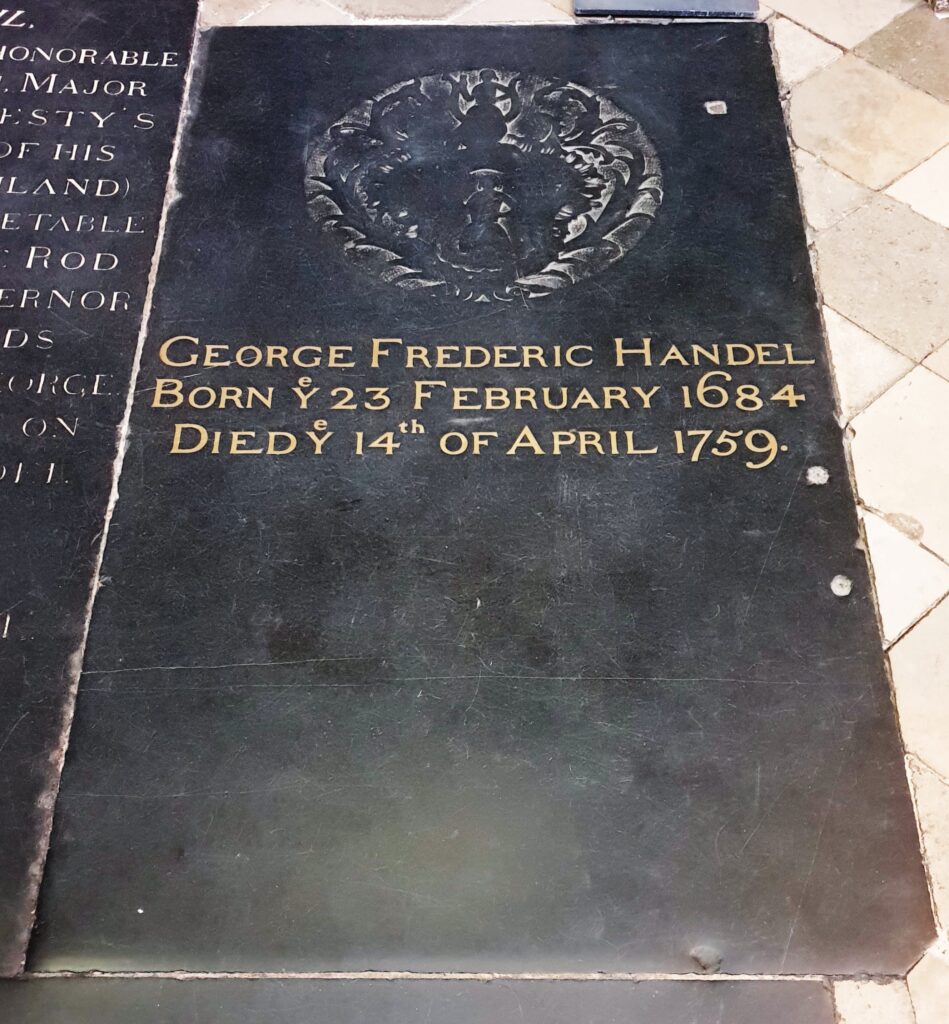

International musical superstars aren’t anything new. You’d think that back in the 1700’s with travelling a lot less comfortable and definitely more time intensive than it is now, that people might stay pretty local, but this wasn’t the case with Handel. He was born in Germany in 1685, but travelled to England in 1712 at the request of the King, George the First. On arrival he received an annual salary of £200 (about $42,000 today). He became a British citizen in 1727 – something which needed an entire Act of Parliament (Handel’s Naturalisation Act) for it take place.

Mixing with the royals. It sounds like becoming a citizen was a lot of work, but that was undoubtedly helped along by his close relations with the Royal Family. He was a favourite of theirs, writing ceremonial music for many state occasions such as Zadok the Priest, which was recently heard again in a Royal setting when it was played at the Coronation of King Charles the Third. Indeed, it’s been heard at every coronation of a British monarch since 1727.

He gathered some inventive and not entirely flattering nicknames. One was ‘The Great Bear’, thanks to his size and nature. That’s not so bad, but perhaps him being called a ‘Barrel of pork and beer’ by composer Hector Berlioz was less flattering… Easy to be rude after his death, we know, but even his contemporary, the composer and organist Charles Burney described him as “somewhat corpulent and unwieldy in motion”.

It seems that Handel had two sides to his personality. On one, he was gentle, kind and compassionate – we’ll come onto his charitable work. On the other, his temper was renowned. He once threatened to throw a soprano out of the window if she didn’t sing his arias correctly!

Handel was not the stereotype of the penniless artist, working for his art. On the contrary he had a keen commercial instinct and knew his audience. Asked for advice by the composer Gluck, he said “You have taken too much trouble over your opera. Here in England that is a mere waste of time. What the English like is something they can beat time to, something that hits them straight on the drum of the ear.”

A generous spirit. As a result of his commercial instinct, Handel wasn’t badly off, and became one of the first celebrity philanthropists. Perhaps most famously he was a benefactor of the Foundling Hospital, Britain’s first home for abandoned babies and children whose parents were not married. He gave a benefit concert for the hospital in 1749, with it being so successful he repeated it every year for the rest of his life. The Foundling charity survives today as Coram (www.coram.org.uk), who still work to improve the lives of children.

Musical neighbors. Handel took up residence at 25 Brook Street, London, in 1723, and stayed there until his death in 1759. He was not to know of course that he’d have a very different but also musical neighbor in due course – Jimi Hendrix moved into the adjoining 23 Brook Street in 1968. Today the building houses the Handel and Hendrix House museum.

A life perhaps too well lived. Handel’s enjoyment of food and drink ultimately probably played a part in his downfall. By his early 40’s he was suffering from acute gout, digestive issues, rheumatic pain and palsy (muscle weakness). This likely also a result of lead poisoning. Lead was used to transport and store wine, and it was even added to wine as a preservative and flavor enhancer. Not only this but the powders used to keep the fashionable wigs of the day white secure to the scalp, and whiter than white, also contained lead. By the end he was going rapidly blind too, even writing in his score for Jeptha, his last Oratorio: ‘Reached here on 13 February 1751, unable to go on owing to weakening of the sight of my left eye’.

Handel died in 1759. His funeral was a grand state affair, with over 3000 people turning out for it. He earned the admiration not just of his public but of many composers that came after him, including Beethoven, who said not only that he was his favorite composer but giving him the accolade of stating that ‘Handel is the greatest and ablest composer.’

Garden of Good and Evil, featuring the music of Handel, runs from 18-21 October. Full details here.