EARLY MUSIC’S “GREATEST GENERATION:” A PERSONAL REMEMBRANCE

Bruce Lamott

George Houle

The recent death of Stanford’s charismatic professor and musician George Houle (1927-2017) gave me pause to think of the giants of Early Music and “historically informed performance” who have left us in recent years. Unfortunately these are names we would never see in those end-of-year “In Memoriam” tributes compiled by the popular media which otherwise include golfers, coaches, film editors, and even the occasional race horse. And yet, without the work of these men and women, our understanding of the music of the Baroque and Renaissance periods–indeed the sound of the music itself–would be sorely lacking.

Laurette Goldberg

I came to Stanford in the early 70’s because of George Houle’s program in Baroque performance practice there, and, though he was absent for the first two years directing the New York Pro Musica, the Music Department was replete with candidates for D.M.A (Doctor of Musical Arts, for performers) and.Ph.D. (musicology) degrees bridging the traditional divide between scholarship and performance. (Dancing pavanes and gavottes on the lawn was required in our curriculum.)

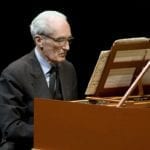

Gustav Leonhardt

Across the Bay, Laurette Goldberg (1932-2005) and Alan Curtis (1934-2015) were at the center of a vibrant Early Music scene that brought legendary artists such as harpsichordist Gustav Leonhardt (1928-2012) and recorder player, baroque flutist Frans Brüggen (1934-2014). These Pied Pipers lured many Bay Area musicians to study in Europe, coming home to create “Amsterdam West” in the environs of the UC Berkeley campus.

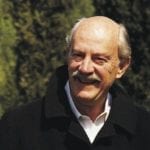

Alan Curtis

Alan Curtis cross-fertilized Berkeley with the European conducting career of his ensemble, Il Complesso Barocco, editing scores and bringing new life to Baroque opera, especially works of the seventeenth century. Harpsichordist Laurette Goldberg, eulogized as the Great Mother of Early Music in the Bay Area, organized and directed an orchestra of period instruments–the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra of the West, as it was known. She created MusicSources, a venue for performance and study, and was at the nexus of the Junior Bach Festival, the San Francisco Early Music Society (SFEMS), and the Berkeley Music Festival and Exhibition, teaching harpsichordists at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music in her “Den of Antiquity.”

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

We’ve also recently lost two prolific conductors and performing artists, Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929-2016) and Christopher Hogwood (1941-2014). Harnoncourt’s recordings of Bach cantatas in collaboration with Gustav Leonhardt and the Vienna Boys Choir and his period instrument orchestra, Concentus Musicus Wien, marked the entry of period instruments (then called “authentic” instruments) into the mainstream recording market, touching off a firestorm of resistance in the “symphonic” (what I call “intuitive,” not “historically uninformed”) performance camp. Like Harnoncourt, Hogwood and his Academy of Ancient Music helped to widen the horizons of historical performance to Mozart and Beethoven, stimulating thinking about a “one-size-fits-all” approach to the multiplicity of styles found from the 17th-19th centuries.

Christopher Hogwood.

The common legacy of these pioneers was their ability to teach and inspire as well as manifest their scholarly study in performance. I venture to say that there is not a performer of Early Music today whose musical DNA does not contain the influence of one of these people, either directly or through their performances, recordings, and editions. As artists in their own rights, each one left us with not only “historically informed” but “historically inspiring” performance practices.