by Scholar-in-Residence Bruce Lamott

Purcell! the Pride and Wonder of the Age,

The Glory of the Temple, and the Stage.

(Henry Hall: Orpheus Britannicus, 1698)

This tribute by a fellow organist from the Chapel Royal commemorates the recent death of Henry Purcell (1659-1695), the foremost English composer of his generation and one of the greatest English musicians of all time. It appeared among several tributes by prominent musicians in the preface to a posthumously published anthology of songs by Purcell, proclaimed by the title as the “British Orpheus.” Only a year older than Mozart at the time of his death, Purcell wrote an extraordinary amount of music in his 36 years, but like Mozart, he leaves us, wondering what might have been.

This program frames the life of Purcell, from one of his earliest works, influenced by the sacred polyphony of the English Renaissance, to his last completed work for the public theatre, reflections of Hall’s reference to “the Temple and the Stage.” Coming from a family of court musicians, as a boy of eight Purcell became a chorister in the Chapel Royal. By eighteen he succeeded Mathew Locke as master of the violins at the court of Charles II, and at twenty he followed John Blow as organist of Westminster Abbey.

Fantasia XI

The fantasias Purcell wrote for strings in 1680 brought together these elements of his musical environment. Fantasia XI demonstrates his facility with counterpoint in the “antique style” (stile antico) of Renaissance sacred music, a style he would have encountered as a boy chorister, epitomized by the works of William Byrd. His application of this vocally conceived style to instruments followed in a long tradition of such compositions by organist/composers, most immediately in the music written for string ensemble by Matthew Locke. Our instrumentation combines the bass viol (viola da gamba) with violin and two violas, members of the increasingly popular Italian violin family that drove the fretted viols to extinction. While these fantasias are a staple repertoire for modern viol consorts (ensembles of the viola da gamba in poppa/momma/and baby bear sizes of bass, tenor, and treble viol, respectively), by Purcell’s time all but the bass viol had faded from use.

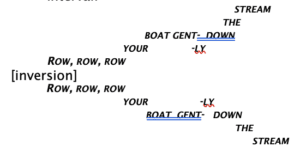

“Fantasia” is an elusive term, revived in modern times by Walt Disney. Composers used this catch-all title for works of adventurous and extravagant explorations of harmony, expression, and caprice but also as the more subtle and sophisticated demonstrations of contrapuntal ingenuity found in Purcell’s fantasias. These are pieces written for the delectation of the performers themselves, intended for “musick’s recreation,” as Purcell’s friend John Playford entitled his collection of viol music in 1682. Fantasia XI is crafted out of two simple five-note scales, one of which ascends, while the other descends immediately thereafter in the same rhythm (called an inversion). The complex texture of continuously interwoven parts that follows consists of these two ideas appearing in all of the parts.

Fantasia XI, dated 19 August 1680, neatly divides into three sections of contrasting textures. After all parts cadence together, the middle section (marked “Drag”) is more chordal, or harmonically conceived, creating the effect of a brief slow movement. Instead of the continuous contrapuntal lines of the first section, it is marked by three repeated chords in opposition to the remaining fourth part. The final section, marked “Brisk,” opens with note values twice as fast as the preceding sections, creating a lively two-measure preamble to the return of the five-note descending scale of the first section. In conclusion, the bass reintroduces the rising scale of the opening measures.

Trio Sonata in A Major, Z. 799

Q: How many players does it take to play a trio sonata? A: Four. The answer to this trick question about this popular genre of chamber music in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries takes into account the presence of the basso continuo, the amalgam of two instruments: a cello or viola da gamba playing the melodic bass line and the harpsichord, playing its implied harmonies. This trio sonata comes from Sonnata’s of III Parts: Two Violins and Basse: To the Organ or Harpsecord, printed for the composer in 1683. Despite its title, the publication contains parts for four instruments: two violins, cello (called basso), and basso continuo, the only difference in the latter two being the presence of chord symbols (figured bass) above the bass line written for the keyboard in the continuo part.

The first movement is a fugue whose subject is announced, fanfare-like, with a sustained note preceding the dotted rhythms characteristic of the French overture. Tracing this single note throughout the texture leads to some unexpected harmonic excursions. The two violins and cello take equal part, and unlike many Bach fugues, the subject (fugue theme) is always present in one of the parts.

The second movement differentiates the two violins from the cello/harpsichord continuo, with the upper parts often playing in parallel motion against the independent bass line. Only at the beginning of the final phrase do the three parts briefly separate in fugal imitation before the violins lock back into step over a sustained bass. A startling shift of key, from A major to a very unrelated F-sharp major introduces a harmonically adventurous chordal section before A major returns in a lively fugue. It begins properly enough, but once again the violins gang into a duet in opposition to the bass.

Trio Sonata in G Minor, Z. 807

The answer to our trick question above is confirmed by the title page of the publication in which this work is found: Ten Sonata’s in Four Parts Compos’d by the Late Mr. Henry Purcell, “Printed by J. Heptinstall for Francess Purcell, Executrix of the Author” in 1697, two years after Purcell’s death. It contains the same four parts found in the earlier publication.

While most trio sonatas consist of a few movements in contrasting tempos and styles, Purcell’s Trio Sonata in G Minor (Z. 807) is a continuous variation form (called a ground bass, or basso ostinato) written over a repeating bass melody whose final note becomes the first note of the following variation in snake-bites-its-tail circularity.

Pieces written on a ground (a term easy to remember “because the bass just keeps grinding away”) were especially popular in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. It found new popularity in the late twentieth century, when variations on a ground by Purcell’s German contemporary Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706) escorted legions of brides down the aisle throughout the world. Purcell would have recognized Pachelbel’s piece to be a “canon upon a ground.” Though Purcell’s two violin parts, unlike Pachelbel’s three, do not play in strict canon (i.e., exact imitation) the semblance between the pieces is striking.

The hypnotic appeal of the repeated bass contrasts with the interplay of the upper parts. While the rhythm and tempo of the ground remain constant, the upper voices create a kaleidoscopic variety of moods and energy, sighing with expressive chromaticism, chasing cat-and-mouse through flurries of passagework, elongating notes in the illusion of a slower tempo, and displacing accents with offbeat syncopation. A plaintive variation leads to an unexpected change of meter, i.e. divisions of the beat into three (triplets) instead of two, characteristic of the leaping French court dance, the gigue. Unlike Pachelbel, however, Purcell’s accumulating energy does not rush headlong to the end but dissolves into rising and falling chromatic lines and pungent dissonances.

The Fairy Queen

Purcell lived during the reign of three British monarchs: Charles II, James II, and William and Mary. When Parliament invited Charles to return to the throne after nine years of exile in France in 1660 following the Civil War which climaxed with his father’s execution, he restored not only the monarchy but also brought with him the extravagance, hedonism, and musical taste of the French court. Church music gave way to secular chamber music–such as the preceding trio sonata–under the Catholic James II , and after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 resulted in his abdication and brought William and Mary to the throne, Purcell no longer held a position as a court musician. They did have the good sense, however, to keep him on the payroll and commission him for occasional works. It was after 1690 that he turned his attention to music for the stage.

Purcell’s last complete work for the theatre was a semi-opera (John Eliot Gardiner calls it a “Restoration variety show”) The Fairy Queen, first performed at the Queen’s Theatre in London on May 2, 1692. The adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream was interspersed with musical “masques” of instrumental music, songs and dances only indirectly related to the themes of the drama. Curtis Price describes it as “not a corruption of Shakespeare’s play but rather an extended meditation on the spell it casts.”

Our sampler plate of instrumental music drawn from the masques, some of Purcell’s finest theatrical music, reflects the English appetite for le goût Français through the dances and musical forms of the French court where Charles II and James lived during their respective exiles. The fanciful titles and charming music spark our imagination of a lavish production that included Fairies, Green Men, and gratuitous exoticism.

The Rondeau was a popular musical form in which contrasting musical episodes alternate with a refrain in the form A-B-A-C-A. Purcell’s best-known rondeau, written for the play Abdelazer, is the theme used in Benjamin Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra: Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell. Contrasted with this quintessentially French form are two British hornpipes, a dance so characteristic of the UK that it was sometimes called angloise on the Continent. The first hornpipe in this group is a rather tame rhythmic alternation of anapests (short-short-long) and dactyls (long-short-short), while the Third Act hornpipe features boldly accents shifting from two groups of three (6/8) to three groups of two (3/4), a type of syncopation known as hemiola.

While Fairies are standard-issue in Shakespeare’s play, Green Men are not. Following the lilting Dance for the Fairies is this stage direction: Four Savages Enter, fright the Fairies away, and Dance an Entry. The skittering scales depicting the nervous energy of the “savages” melt into mawkish chromaticism at the midpoint, perhaps regrets that the fairies have fled. The second half is a send-up of the dotted rhythms characteristic of the French overture, suggesting a comic image of rustics aping French courtly manners.

The final scene is a decidedly un-Shakespearean “Prospect of a Chinese Garden,” feeding the audience’s taste for chinoiserie with ethnically insensitive roles for a Chinese Man and Woman (named Daphne) that fortunately need not concern us here. There is nothing Chinese about their very French Chaconne that concludes the whole production. Like the Trio Sonata in G Minor earlier in this program, it is a variation form based on a ground, with episodes in major and minor, a variation without basso continuo, and an accumulating energy that leads to the theatrical conclusion.