Bach’s Christmas Oratorio

December 9–12, 2021

The perfect start to the holiday season, Bach’s Christmas Oratorio combines the drama of an oratorio with the religiosity of a cantata, resulting in a piece of astonishingly vivid musical color and intensity of emotion—and sure to be thrillingly realized by the award-winning Philharmonia Chorale.

BACH Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248

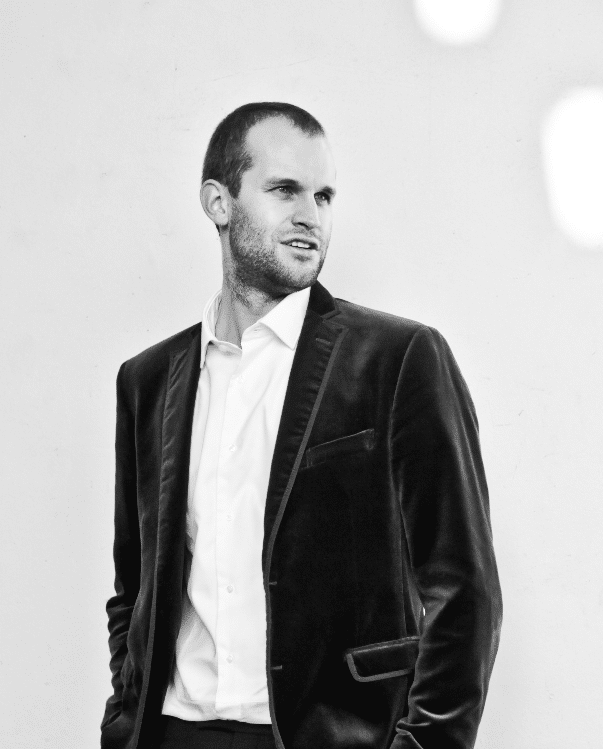

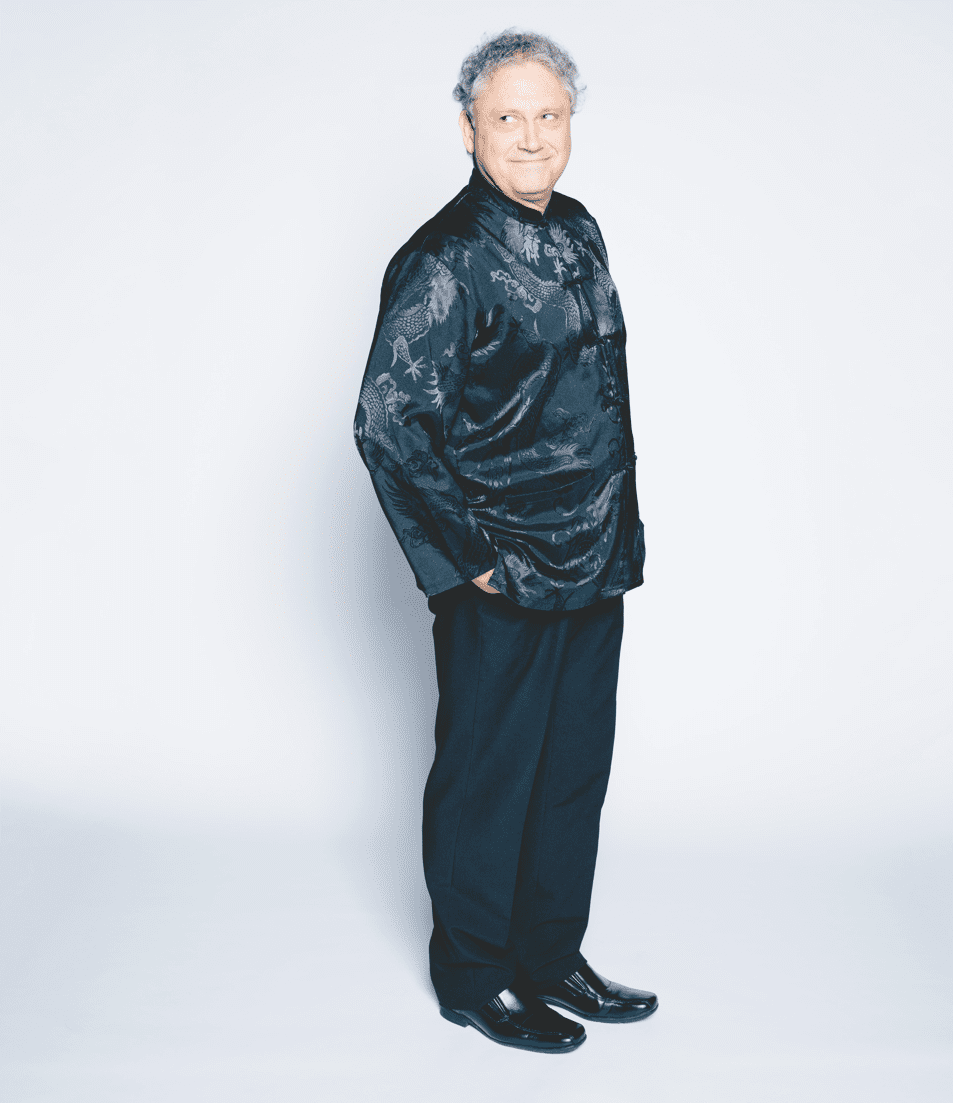

Richard Egarr, conductor

Lydia Teuscher, soprano

Avery Amereau, contralto

Gwilym Bowen, tenor

Ashley Riches, bass-baritone

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale

”Egarr...heightened every moment of drama and evoked a sense of magic."

Financial Times

About Bach’s Christmas Oratorio

The perfect start to the holiday season, Bach’s Christmas Oratorio combines the drama of an oratorio with the religiosity of a cantata, resulting in a piece of astonishingly vivid musical color and intensity of emotion—and sure to be thrillingly realized by the award-winning Philharmonia Chorale.

A top-drawer cast, many making their PBO debuts, is led by Music Director Richard Egarr for an unmissable highlight of PBO’s season.

The Music

BACH Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248

Program Notes

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248

In 1723, Johann Sebastian Bach took the job that would come to define his career: Cantor at St Thomas’s Church in Leipzig. The post handed him overall responsibility for the music not just in that church, but in all the Saxon city’s major churches.

Bach would remain in the job for 27 years. It was a productive and transformative if not entirely happy arrangement. But then, Bach was a natural dissident—impatient in the face of bureaucracy and philistinism, driven by a creative ambition that frequently outstretched the resources available to him, despite his occasional pragmatism.

Still, Bach was determined to make the very best of those resources. In Leipzig, he hit the ground running and set out his stall from the start. From 30 May 1723—which that year formed the First Sunday of Trinity in the Lutheran church’s calendar—he started writing a series of bespoke cantatas for each Sunday and Feast Day of the ecclesiastical year, tailored to St Thomas’s Church’s musicians. Later in the 1720s, the project would be complemented by a further cycle and by musical settings of the Passion—the story of Christ’s final days on earth.

Bach often considered his daily work at St Thomas’s an uphill struggle, and just as often complained of a lack of support. The more frustrated he became with the limitations and leadership attitudes at St Thomas’s Church, the more he sought stimulation elsewhere. He involved himself in a student music society in Leipzig that allowed him to write plenty of secular and purely instrumental music.

By the 1730s, no longer feeling the pressure to write weekly cantatas for St Thomas’s (those he had written already could simply be re-used), Bach started to think on a bigger scale. Prompted partly by his work on the Passions, he considered the creation of grand new works, on a large scale, that could incorporate and refine music he had already written.

Bach’s tidy mind was naturally drawn to large forms neatly divisible into modular parts—structures whose individual sections could stand alone, but would resonate more when brought together or treated as a single cycle or journey. In 1734, Bach turned his mind to one such project. He designed an oratorio in six parts, the performance of which would span the two weeks from Christmas to Epiphany.

So, Bach’s so-called Christmas Oratorio, rather like Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen—would not originally have been heard in one sitting. Its opening chapter was performed on Christmas Day, 1734, with Parts 2 and 3 following on the 26 and 27 December. Part 4 was performed on New Year’s Day, Part 5 on the following Sunday, and Part 6 on the Feast of the Epiphany (6 January).

In narrative terms, the schedule presents a journey from the birth of Christ, continuing through the adoration of the baby Jesus by shepherds, his circumcision and naming, the journeying of the Magi from the East and to the eventual arrival of the Magi with their gifts.

Such a cycle demanded a great deal of music. But it was always Bach’s intention, according to his new modus operandi, to re-use music he had already written.

A year earlier, in 1733, Bach had composed secular cantatas to celebrate the birthday of Prince Friedrich of Saxony (Lasst uns sorgen, BWV213) and Maria Josepha, later Electress of Saxony (Tönet ihr Pauken!, BWV214). The texts for both these works were weak. But the music was good, and if it wasn’t reused, it would never be heard again.

In total, eleven of the Christmas Oratorio’s movements are lifted straight from these cantatas. Some musicologists have proposed that the oratorio’s Part 6 is based entirely on a lost ‘Michaelmas Cantata’ dating from September 1734. What’s certain is that all the oratorio’s text was entirely new—specially fashioned in 1734 by Christian Friedrich Henrici, the poet known simply as ‘Picander.’

Bach’s handling of that text would borrow a device from his own John and Matthew Passion settings of the previous decade, in which a tenor takes narrative responsibility. Thus the story of the birth of Christ, as recounted in the Gospels according to Luke and Matthew, is recounted by a tenor voice in a role roughly equivalent to that of the ‘evangelist’ in Bach’s Passions. When the tenor is simply relaying elements of the story in the Christmas Oratorio, the accompaniment is dry (‘secco’) recitative: speech-song with a bare accompaniment rooted on keyboard or cello.

Unlike the Passions, there is little acting-out here and almost no character interaction. The six cantatas are more abstract and meditative—part of Bach’s broader reflection on the life of Christ that itself forms a trilogy with the Easter and Ascension Oratorios that would follow in 1735. The Christmas Oratorio contains plenteous symbolism and theological observation, but is otherwise a work of joyful optimism conceived as a life-enhancing, joy-giving musical experience (Bach even stops short, in his recounting of Herod’s role in events, of covering the massacre of the innocents).

Each cantata is different and self-contained, standing effectively on its own. And yet Bach still manages to bind all six together, conceiving a broad scheme across the whole cycle in which the basic key starts and finishes in D major, journeying satisfyingly to G, D, F and A in between. Chorale tunes that would have been familiar to Bach’s congregation in Leipzig are deployed in each part, with the same chorale featuring in Part 1 as in Part 6. This, in fact, is a chorale familiar from Bach’s St Matthew Passion—a unifying motto for Bach’s listeners, and a subtle reminder that Jesus’s human life on earth was destined to end in suffering.

Musicologists are often drawn to the particular quality of the chorales in the Christmas Oratorio. Despite recycling plenty of music elsewhere, Bach dresses these known and much-used tunes in entirely new harmonic clothing. As a result, chorales that feel richer and more imaginative but at the same time clearer and more direct. According to the conductor John Eliot Gardiner, the Christmas Oratorio’s chorales ‘emerge more naturally from the intersection of voices…and have an even stronger sense of just proportion and balance.’

Bach’s judgment when it came to re-using his own music was impeccable. That much is evident right from the start of the Christmas Oratorio’s opening cantata, a frolicking chorus in D major cut-and-pasted straight from the cantata for Maria Josepha. The rhythmic choral outbursts that once proclaimed Tönet, ihr pauken! (‘resound, you drums’) now exhort us to Jauchzet, frohlocket! (‘shout, rejoice’). The drums remain in place but don’t feel at all incongruous.

Similarly, the ensuing aria that calls on the faithful to prepare themselves ‘with tender affection’ (Bereite dich Zion) is reworked from a moment in the secular ‘Hercules Cantata’ BWV213, in which Hercules denounces lust.

Bach biographer Nicholas Kenyon has written of the composer’s knowing irony in transferring the aria for trumpet and bass voice, Grosser Herr. In its original BWV214 setting, the music proclaimed the glory of Maria Josepha; here it describes a ‘dearest savior’ who ‘cares little for the glories of earth.’ Bach wouldn’t have seen a contradiction. According to Lutheran teaching, earthbound rulers were vessels for sacred authority, while the glory of God was readily apparent in the mostly humble of creations—a flower, an act of benevolence, a newborn baby.

The ‘Pastoral Symphony’ that opens Part 2 is a conscious reference on Bach’s behalf to the Italian tradition for ‘Christmas concertos’ propagated by the likes of Corelli and Manfredini. Bach’s response, laced with the beautiful, mellow sound of a pair of oboes da caccia, sets the scene for the coming view of shepherds tending their flocks (as recounted by the tenor evangelist).

The lilting alto aria ‘Schlafe, mein Liebster’—another movement drawn from a secular forbear—sees the infant Jesus rocked to sleep, a solo flute fluttering above the voice almost like a pacifying mobile above an infant’s cot. The chorus of rejoicing angels that follows, ‘Ehre sei Gott in der Hohe’, justifies Gardiner’s comment that the composer’s ‘angelic choir would appear to consist entirely of expert contrapuntists.’ The reference is to music of complex, agile moving parts.

Part 3 tells of the shepherd’s journey to Bethlehem. It launches with what was originally the final chorus of BWV214—another bright, contrapuntal weaving of voices that here praise the ‘Herrscher des Himmels’ (‘Lord of Heaven’). The rest of the music is notably for its focus on the abstract concept of faith. A rustic duet for soprano and bass, with two oboes for company, reminds the congregations that God’s mercy and forgiveness has set them free; the darker aria for also and violin then uses the rush of Mary’s first experience of motherhood as an instruction to the faithful to ‘keep this miracle safe within.’

Trumpets feature in Parts 1, 3 and 6 but Part 4 introduces horns with an opening chorus in the hunting style derived from the opening of BWV213. This more down-to-earth musical style with obvious vernacular connections reflects the cantata’s focus on the baby Jesus (and his circumcision), rather than the deity in heaven. When the child is named, the sopranos of the choir weave a chorale around speechsong statements from the bass soloist—an enchanting and unusual structure.

Later comes the celebrated ‘echo aria’ for soprano and oboe (also drawn from BWV213). It is a meeting of the simple and the complex typical of Bach. A chorus, representing humanity, responds to the soprano’s confusion of feelings and questions at the arrival of Christ with reassuringly direct statements of ‘yes’ and ‘no’. And yet, the relationship between the music’s three elements (voice, oboe and chorus) is never predictable. The tenor needs extreme agility for his aria with two violins, ‘Ich will nur dir zu Ehren leben,’ built on a leaping octave and strings of repeated notes with little apparent room to take a breath.

The exhilarating chorus that opens Part 5—ecstatically and joyously greeting the new born child with tripping rhythms—was specially written by Bach. The ensuing cantata tells of the appearance of the three wise men and their enquiries as to the location of the newborn. After a bass aria lightly personifying one of the wise men, we hear a trio for soprano, alto, tenor and violin solo described by Kenyon as ‘the nearest Bach ever came to a serious operatic ensemble.’ In apparent conversation, the soprano and tenor ask when the messiah will appear, only for the alto to respond in half-interruption that ‘he is already here.’

The Feast of the Epiphany marks the arrival of the wise men and the revelation of Jesus as God incarnate. With this summation of the Christmas story, Bach lifts his oratorio onto a new level of grandeur and exuberance for its sixth and final cantata. But there’s a seam of darkness, mystery and caution in this last installment in the sequence. The opening chorus veers into minor keys, before the soprano’s recitative and aria obliquely reference Herod’s interrogation of the wise men—a position taken up later by the tenor. A special four-voiced recitative leads to the proclamation of the Passion chorale heard in Part 1, here adorned with swirling trumpets and spirited by decorative and imitative wind and strings. The message of Christ avenging death unites the most joyous elements of Christmas and Easter.

And so ended the ‘season of celebration’ that took place in Leipzig for fourteen days straddling 1734 and 1735. Bach had taken his congregation in the city on an exceptional journey in words and sounds; in an age before recording and broadcasting, this would likely have been the only sophisticated music they heard all through the festive season. Whether or not the Christmas Oratorio was ever heard again in Bach’s lifetime remains a mystery.

Program notes by Andrew Mellor © 2021

Pre-Concert Conversations

Join members of the Chorale 45 minutes before each concert for conversations on the joyous experience of returning to singing and working with Music Director Richard Egarr.