Mozart the Radical

February 10–13, 2022

Mozart was a composer who loved to test boundaries, and in his Symphony No. 38 you hear him pushing the orchestra of the day to the limit, expanding the horizons of the symphony. It’s a veritable smorgasbord of invention, a riot of creativity.

MOZART Concerto for Fortepiano No. 24 in C minor, K. 491

MOZART “Ch’io mi scordi di te? … Non temer, amato bene”, K. 505

MOZART “Bella mia fiamma, addio”, K. 528

MOZART Symphony No. 38 in D major, K. 504 “Prague”

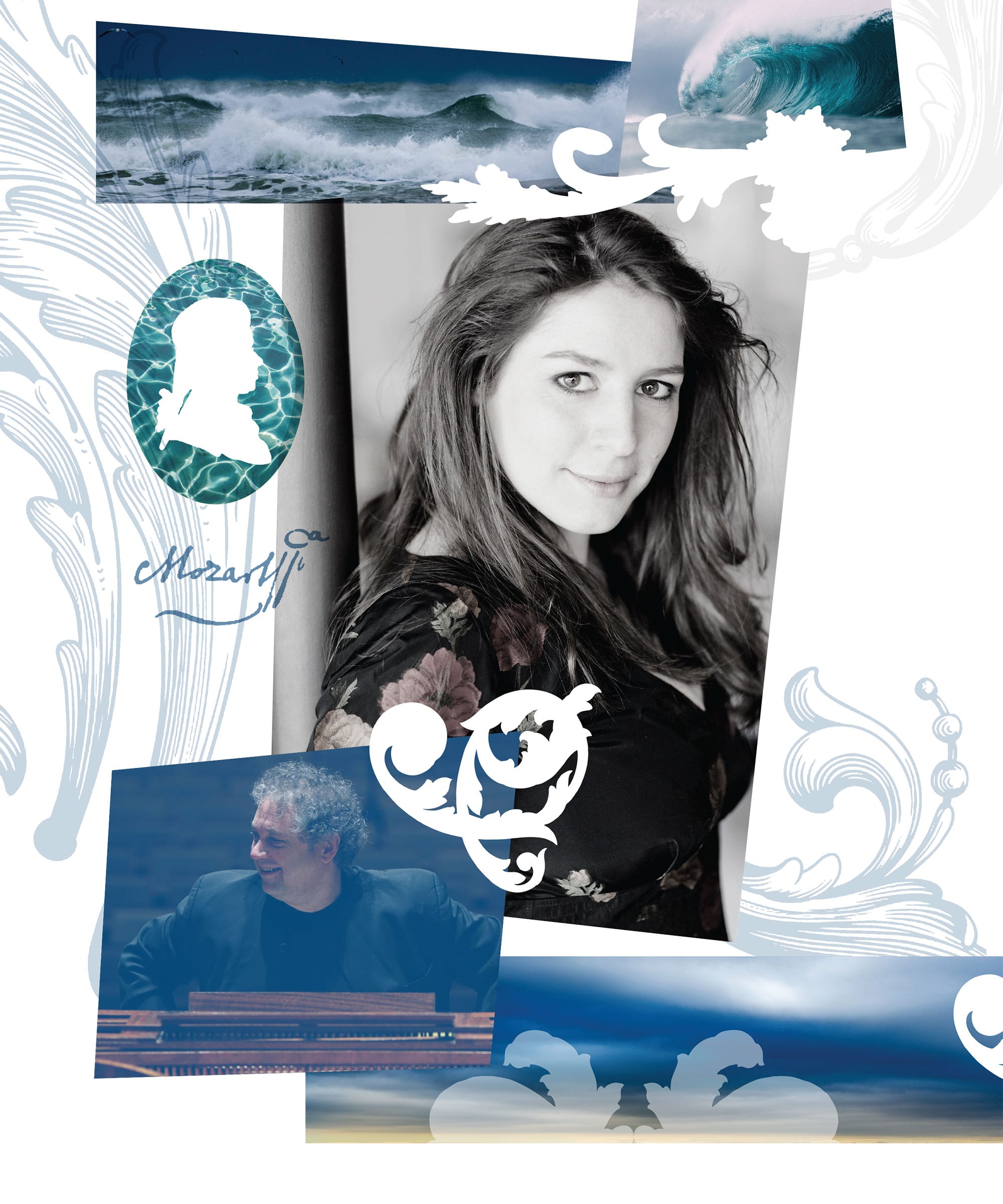

Richard Egarr, conductor and fortepiano

Elizabeth Watts, soprano

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra

The length of this performance is 100min.

”One of the most beautiful voices Britain has produced in a generation."

International Record Review

About Mozart the Radical

Mozart was a composer who loved to test boundaries, and in his Symphony No. 38 you hear him pushing the orchestra of the day to the limit, expanding the horizons of the symphony. It’s a veritable smorgasbord of invention, a riot of creativity.

At the start of the finale, Mozart cheekily squeezes in a little snippet of music from The Marriage of Figaro, so it’s only appropriate that we showcase some of his operatic writing too, including the concert aria “Will I forget you? … Fear not, beloved,” here with Elizabeth Watts in her PBO debut.

Dark, tragic and passionate, Mozart’s Concerto No. 24 was admired by none other than Beethoven, and for this concert the original textures and sounds of the work are revealed with Richard Egarr performing it on a fortepiano, the instrument for which it was written.

The Music

MOZART Concerto for Fortepiano No. 24 in C minor, K. 491

MOZART “Ch’io mi scordi di te? … Non temer, amato bene”, K. 505

[intermission]

MOZART “Bella mia fiamma, addio”, K. 528

MOZART Symphony No. 38 in D major, K. 504 “Prague”

Program Notes

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Piano Concerto No 24 in C minor, K491

In 1781, Mozart went freelance. It wasn’t entirely planned. The composer had been fired by the Archbishop of Salzburg, dismissed with the ‘kick to my arse’ he so enjoyed recalling. Deep down, Mozart knew the change would do him good. He moved to Vienna, where his industry, talent and imagination carried him to success. But so did a hugely popular and fast-developing piece of equipment: the piano.

As Handel had before him, Mozart cocked an ear towards the slipstream of public taste, and got wise to what his ‘customers’ wanted. What they wanted was piano music played by him. In 1784 alone, Mozart wrote six piano concertos to play at his own subscription concerts in Vienna. Ticket income was healthy, and for a time Mozart was cruising.

Then, in 1785, he changed gear. Over the next two years, Mozart significantly reduced his quantitative output of piano concertos but massively increased their depth, expression and architectural imagination in inverse proportion. His concerto numbered 20, written and performed in 1785, got the Viennese talking by dint of its predominating minor key (unusual at the time). All the while, Mozart was taking advantage of the instrument’s increasing capacity for expression and dynamic variance.

A year later in 1786, Mozart delivered something similar but without that concerto’s light relief. He unveiled a concerto in C minor that maintains its tragic mood right to the very end. This concerto’s music is emphatically repetitious and anxiously chromatic, and also more ready to devolve its textures down into instrumental groups. It touches upon all twelve notes of the chromatic scale within the first eleven bars of its exposition (there are 88 more still to come). The unusual three-in-a-bar gait, the leaps through awkward ‘seventh’ intervals and the nervous energy all look beyond Classicism’s principles of symmetry and perfection towards something more personal, more Romantic.

There is balm (the E flat major Larghetto) and there is humor (the two major-key diversions among the finale’s set of variations on a sinister dance). There is also a new status for woodwind instruments: in the Larghetto, piano and winds seem to hang on each others words while in the final movement theme and variations, the woodwinds take on the second variation. Otherwise, there can be little doubt that Mozart’s vision for the piano concerto as more than an entertainment has come to full fruition here.

The score calls for Mozart’s biggest orchestra yet in a concerto (oboes and clarinets). It carries with it a feeling of grandeur fueled by defiance, laying groundwork for Beethoven’s concertos and maybe even putting him on to the particular qualities of the key of C minor. The musicologist Wolfgang Rehm has referred to the concerto’s ‘veiled tragedy, suppressed sorrow and ominous tension’.

‘Ch’io mi scordi di te?’ K505

In the final days of 1786, Mozart was moved to write something deeply personal. Nancy Storace, the singer who had created the part of Susanna in his opera The Marriage of Figaro months earlier, announced her departure for London. In bidding her a musical farewell, Mozart turned to a valedictory text he’d already used for the opera Idomeneo, and set it as an aria ‘for Mlle Storace and me’.

The Recitative and Aria Ch’io mi scordi di te? is rather more than both those things. It is effectively an exceptional hybrid of piano concerto and aria in which pianist and singer are bound in a heartfelt, intimate exchange. There has long been speculation that Mozart wanted more from Storace than good friendship.

His aria–words and music–would appear to confess as much. The music starts out full of tenderness, the shapely vocal line alternating with commentary and decoration from the piano, which occasionally joins it in duet. But Mozart soon draws us into a multi-shaded drama in which voice and piano (and orchestra) are inseparably intertwined.

‘Bella mia fiamma, addio’ K528

Mozart produced quite a few stand-alone arias throughout his career. They were often written for insertion into operas by other composers, or as test pieces with which the younger, more inexperienced Mozart flexed his dramatic muscles.

This example, like its predecessor heard earlier tonight, had a more personal genesis. While his opera Don Giovanni was rehearsed and premiered in Prague in the Autumn of 1787, Mozart stayed with his friend the composer František Xaver Dušek on the outskirts of the city. Dušek’s wife, the soprano Josepha Hambacher, cajoled Mozart into writing this aria for her before he took his leave of their villa, reportedly locking him in a garden pavilion until he had done so.

Mozart, always up for a caper, got his revenge. He is alleged to have warned Josepha that she could only take possession of the aria if she could perform it faultlessly at first sight. Not too serious a problem for an experienced singer–until Mozart lined Josepha’s aria with technical traps. One passage in particular finds its way to extraordinary harmonic complexity that was surely designed to challenge a sight-reader (and tease Josepha)–listen out for it on the words ‘Quest’affanno, questo passo è terribile per me.’

The text allowed Mozart this depth of expression. It was borrowed from a libretto by Michele Sarcone already used by one of the composer’s contemporaries (an old method), and recounts an episode from the Proserpina myth in which Titano, commanded to die and leave his beloved, takes his leave for the last time with extreme anguish. It drew intensity and pathos from Mozart. Even when imprisoned in a greenhouse by a friend playing a prank, the composer’s dramatic powers are formidable.

Symphony No 38 in D major K504, Prague

Mozart didn’t just have a good time with the Dušeks; he adored Prague and the city apparently adored him back. The Bohemian capital furnished Mozart with lucrative commissions and welcomed the fruits of those commissions with open arms–offering Mozart all the unqualified admiration and success he’d started to find elusive in Vienna. ‘My Praguers understand me,’ Mozart is reported to have said of his audiences in the city.

The composer’s so-called ‘Prague’ symphony has come to represent that mutual fertility, warmth and joy. It actually pre-dates the success of Don Giovanni, and was written in December 1786–at the same time as the piano concerto heard earlier tonight – as a gift to the city as Mozart travelled there to view its production of The Marriage of Figaro. Early in 1787 the symphony was given its first performance at the Prague National Theatre.

Mozart returned the respect offered him by Prague’s audiences with an intelligent, profound and witty symphony. Famously lacking a minuet – the most undemanding of symphonic movements–it opens with a statuesque, D-minor gravity that seems to foreshadow Don Giovanni (the opera’s music might well have been brewing inside Mozart already). This pregnant, straining opening material, which is not heard explicitly again, soon gives way to music of thrilling momentum in which the orchestra is nudged onto new paths by a keen oboe.

What follows is music of complex, intimate argument that once again appears to credit the citizens of Prague with keen ears. Mozart plunges his orchestra into a deep discussion of musical ideas, and a forward-looking symphonic debate emerges rivalled only in Mozart’s output by the later Jupiter symphony. There is contrast and effervescence on the surface, while a consistent undercurrent appears to root the music in place.

The rigorous conversation extends to the slow movement. This is a serene exercise for woodwind, horns and strings that possibly owes its text-like pace to the Prague opera swimming around in Mozart’s head. The nimble theme that opens the compelling finale (actually a quote from Figaro) introduces a rhythmic motif that dominates the movement in various adapted forms–by turns sumptuous and perky–while also providing the basis of a witty and spirited conclusion. Mozart pushes the harmonic envelope in this movement with even more exploration of chromatics and dissonance and the most multi-layered web of voices a symphonic structure had yet been forced to sustain. But he also ensures the symphonic circle is formally closed: listen carefully for a subtle recycling of the bass arpeggios that underpinned the symphony’s imposing opening.

Prague, Music and Mozart

Prague was an international city long before San Francisco, London or Berlin. Situated in a position of vital strategic importance on the River Vltava, it fell under the influence and rule of a succession of foreign regimes, most famously the Habsburg dynasty. The Habsburgs established dominance in Prague in the 1600s, when it was capital of the area known as Bohemia.

Initially, music had a rough ride under the Habsburgs. On their watch Prague became a provincial rather than imperial capital, leading to an exodus of aristocrats to Vienna (musicians and artist quickly followed). Into the 17th and 18th centuries music did flourish, but it was far from native: imported styles and talents reflecting the traditions of other countries came to dominate musical life.

One of those influences was Italian–specifically Italian opera. It grew in popularity among Prague’s aristocrats through the Baroque and into the Classical periods. Without an operatic tradition of its own, Prague once again looked elsewhere for influence and an injection of talent.

In 1782 Prague staged Mozart’s German language opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail and, four years later, the Italian-sung The Marriage of Figaro. Both went down a treat, and the composer was invited to Prague to view the latter production. Once there he conducted the symphony written for the city performed tonight. So impressed was the impresario Pasquale Bondini with Mozart that he commissioned an opera from the composer to be completed that same year: Don Giovanni.

Program notes by Andrew Mellor © 2022