Handel’s Oratorio Choirs

By Bruce Lamott

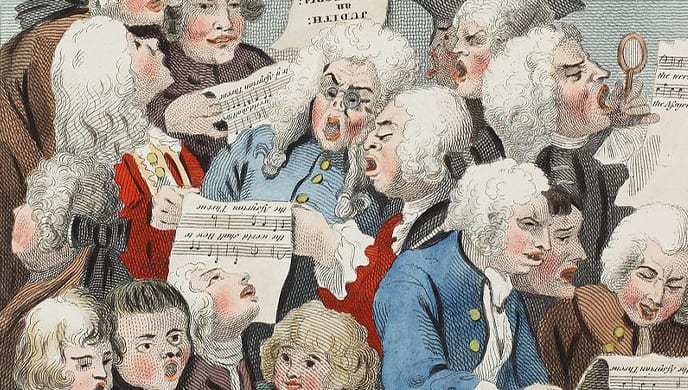

“A Chorus of Singers” by William Hogarth, 1732

While there has been a long-running controversy among musicologists and conductors about the makeup of Bach’s choirs (one-to-a-part? four-to-a-part? more-to-a-part-if-he-could’ve afforded it?) the historical record is clear about the gender and number of singers in Handel’s oratorio choirs. Thanks to St. Paul’s admonition of “Let your women keep silence in the churches” (I Corinthians 14:34), it’s unlikely that Handel ever heard female choristers either in his native Lutheran or adoptive Anglican churches, not to mention sojourn in Catholic Rome, where women were prohibited even from appearing in opera.

In the Anglican churches of London, the configuration of voices was the same: boys with unchanged voices sang soprano, boys with lower voices and adult falsettists sang alto, and men sang tenor and bass. In England, castratos sang only solo roles in opera and occasionally in oratorios, not in church choirs (as they did in Italy and Spain). The number of singers who performed in Handel’s oratorios is uncertain but was likely to be four to seven on a part.

Recruitment of choristers for oratorios was not always smooth sailing. For the Dublin premiere of Messiah in 1742, Handel used choristers from Christ Church and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, whose elderly—and increasingly senile—Dean Jonathan Swift at first scathingly rescinded his permission and resolution to “punish such vicars as shall ever appear there as songsters, fiddlers, pipers, trumpeters, drummers, drum-majors, or in any sonal quality, according to the flagitious aggravations of their respective disobedience, rebellion, perfidy, and ingratitude.” There was particular opposition to choir boys ever taking acting roles on stage and the insistence that they hold musical scores.

“St Paul’s Cathedral” by Robert Trevitt, London 1706

By the time Handel’s oratorio Judas Maccabaeus was first performed at Covent Garden on April 1, 1747, his favored position with the Hanoverian Royals gave him easy access to the Chapel Royal choristers who sang at Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s Cathedral. The oratorio is endowed with eleven choruses which represent the Israelite people in a wide range of emotions from elegiac to bellicose. Women sang in the oratorios only in solo roles: the soprano Elisabetta de Gambarini as First Israelite Woman, and mezzo-soprano Caterina Galli in the triple roles of Second Israelite Woman, Israelite Man, and Priest—proof of Handel’s gender-neutrality when it came to casting.

Although Philharmonia is committed to the principles of “historically informed performance,” the soprano and alto parts in the Philharmonia Chorale are sung by adult women, sometimes with the occasional male alto countertenor. Because the onset of puberty for both sexes was much later in the 1700s than it is today—Haydn’s voice broke when he was 16, others as late as 18—most of Handel’s “boy” sopranos were actually technically proficient teenagers, trained in the rigorous choir schools of English cathedrals. His theaters were also acoustically more enhancing and smaller than those in which we perform; for example, the parterre (what we know as “orchestra seats”) of his Covent Garden would extend only to our Row K. Just as slavish adherence to historical “authenticity” has been—fortunately—necessitated by the extinction of the castrato and his replacement by mezzo-soprano or countertenor soloists, the substitution of technically accomplished female singers in the Philharmonia Chorale are “historically informed” by knowing that the parts they are singing were once performed by men and boys.

Experience the award-winning voices of Philharmonia Chorale alongside a starry line-up of soloists including soprano Robin Johannsen, mezzo-soprano Sara Couden, baritone William Berger, and tenor Nicholas Phan in the title role in Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus!