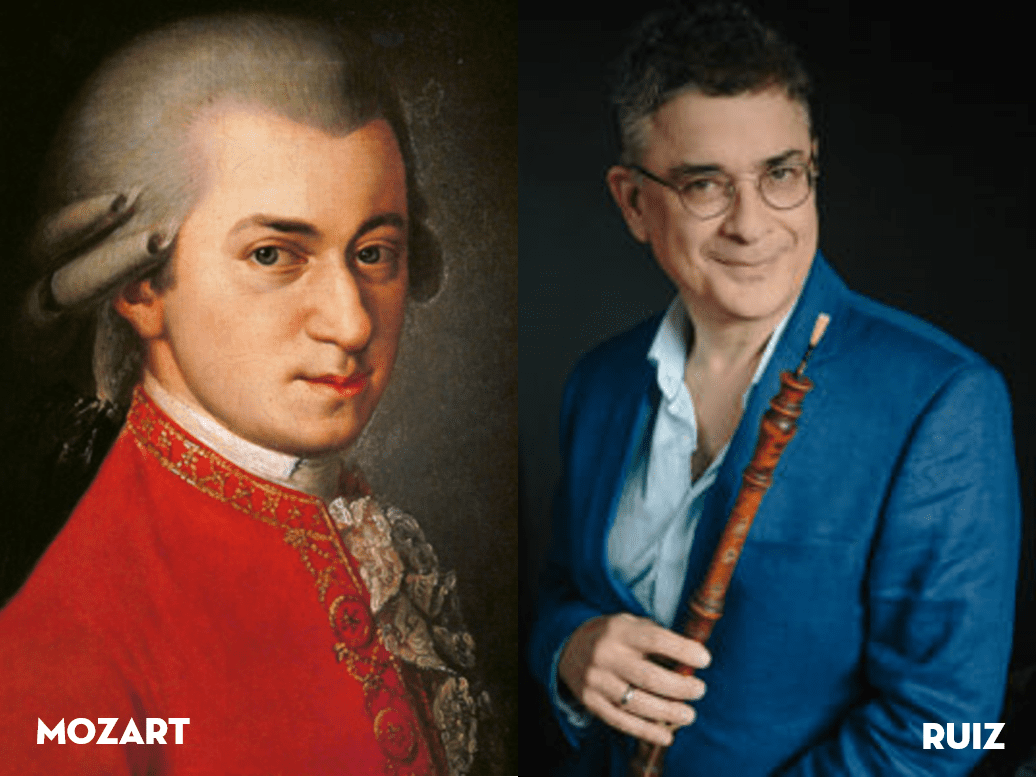

The Story of Mozart’s Thought-Lost Oboe Concerto

By Gonzalo X. Ruiz

In the early 20th century scholars knew that in 1777, as he was getting ready to leave Salzburg for Mannheim and Paris, Mozart wrote an oboe concerto for his colleague Giuseppe Ferlendis. The oboist seemed thrilled with the new piece, and performed it several times. Friedrich Ramm, another oboist whom Mozart befriended in Mannheim soon after that, took up the piece as his “cheval de bataille”, in the words of the composer. All this is recounted in letters to his father Leopold Mozart. Although the work itself apparently had not survived, its identity was suspected, because later that same year Mozart tried to pass off an existing concerto as a newly commissioned flute concerto in D major, a ruse that was quickly discovered by his patron, who then refused payment.

The hunch that this recycled work was the lost oboe concerto was confirmed when a set of parts dating from the 1790’s were discovered in 1920 by Bernhard Paumgartner at the Mozarteum in Salzburg. This was the familiar flute concerto but in C major, and for oboe. The orchestra parts were identical except for some copyist mistakes, and the oboe solo seemed in most passages to be a slightly simpler version of the flute concerto so the immediate assumption was that here was the original version, and it was universally adopted by oboists. However, the theory that Mozart would have taken the time to improve the solo part as part of a transposition job he had turned over to a copyist always seemed suspect. Not only is the flute version more ornate, but the differences in the allegedly original oboe part seem clumsier, less Mozartean. A score in C major found in Vienna at the library of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde that was not noticed until much later seems to settle all these questions. Although it does not specify the solo instrument, it is identical to the flute concerto in D, not only in the orchestra parts but also in the solo. It now appears that the beloved oboe concerto as it was performed since its discovery is actually a reworking by or for an oboist who wanted to avoid playing the trickier bits in the outer movements, which were replaced with simplifications, some more successful than others.

The simplest explanation is most likely correct: Mozart took his existing oboe concerto, and had it transposed without any significant changes. The Salzburg parts, while they confirmed the oboe concerto’s identity, do not in fact represent the original, but a later, slightly corrupted version of it. The flute reworking that Mozart tried to pass off as a new piece, in fact preserves the original, as confirmed by the Vienna score, and is what I play.

Witness this long-lost concerto and its fascinating story brought to musical life by GRAMMY-winning guest conductor Jeannette Sorrell and one of the country’s eminent woodwind soloists—PBO’s own Gonzalo X. Ruiz!