Last month, countertenor Iestyn Davies and lutist Thomas Dunford gave a stunning concert of “greatest hits” from the 17th century found in a collection titled A Musical Banquet. Whether or not you made it to the concert, you’ll definitely want to learn more about this fascinating publication.

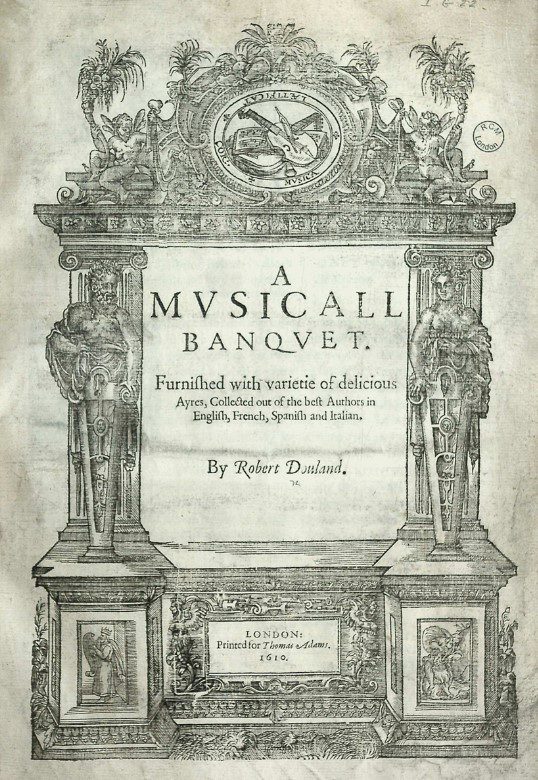

A Musical Banquet

If a musically inclined individual were to pick up an instrument with which to idly entertain themselves or others in the sixteenth-century, that instrument would probably have been a lute. These days, the guitar— the lute’s most obvious contemporary descendent—occupies much the same position. Like no other instrument, the lute was at once a social tool and companion in solitude.

The plucked, stringed and fretted instrument is thought to have originated in the Arab world, entering Europe via Moorish Spain. As the 1500s got going in earnest it became particularly fashionable in an England, flourishing under pleasure-loving Tudor monarchs, including the lute-playing Henry VIII. Musical literacy was growing among the burgeoning middle classes. But while madrigals in divided voice parts required teamwork, rehearsal and multiple participants (and the printing of individual parts to read), accompanying oneself in song on the lute did not. Lutes were mobile, handy, personal and easily entwined with the equally fashionable poetry of the day. They encouraged improvisation and exploration.

The pre-eminent English exponent of the art of the lute at this time was John Dowland (1563-1626), a musician whose influence spread far and wide and whose melodies were being borrowed by composers for decades after his death. Dowland was a child prodigy and also a cosmopolitan European. His first job was in France, where he worked for the English ambassador in Paris. In addition to England, Dowland also worked in Germany, Italy and Denmark. Some say his experiences in the latter country may have inspired Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The two men knew each others’ work. Theatre performances at the time frequently paused to take in a lute song.

By 1610, at the age of 47, Dowland had become travel weary. He returned home to his family for good (they had often stayed behind when he fulfilled long contracts abroad). That year, Dowland’s son Robert, a 19-year-old who would later become lutenist to the English monarch as his father had been before him, marked his father’s return with a major publication: A Musical Banquet.

In fact, the full title was a little grander: A Musicall Banquet furnished with varietie of delicious Ayres / Collected out of the best Authors in English, French, Spanish and Italian. Robert wrote in the publication’s preface that the songs included therein had been ‘gathered out of the labours of the rarest and most judicious Masters of Music that either now are or have lately lived in Christendom.’

In other words, this was a ‘greatest hits’ of European lute song, reflecting the state of the art in the first decade of the 1600s. There can be little doubt that Dowland senior stood behind the publication’s contents, containing as it does music from countries in which he had worked but which his son had not so much as visited. That said, some of those works would have travelled to England and other countries via separate publications and collections.

It is striking to consider, that even in the earliest years of the seventeenth-century, music was becoming a cosmopolitan, international language with the beginnings of a cross-fertilization of styles. Largely thanks to Dowland, English lute song was absorbing continental influences. The 1610 publication demonstrates and celebrates that.

About the Music

In A Grove Most Rich of Shade sets eight stanzas by Sir Philip Sidney, poet and brother of the publication’s dedicatee, Sir Robert Sidney. The stanzas are taken from Sidney’s sequence of sonnets Astrophel and Stella, a bittersweet reflection on love and desire adapted and Anglicized from Petrarch and borrowing the Italian’s rhyme scheme (the poem will crop up twice more over the course of the banquet). The melody, though, is French—commandeered by Dowland from Charles Tessier, a lutenist from the Court of Henri IV whose travels took him to London in the 1580s, just when Sidney was at work on his poem.

Change Thy Mind Since She Doth Change reflects the tendency of some lute songs of the period to express first-person frustration, in this case a complaint against betrayal as annunciated by Robert Devereux’s words and set to Richard Martin’s music, which criticize his own sister Penelope (also Sidney’s ‘Stella’). Devereux was beheaded by Queen Elizabeath I in 1601. Little is known of Martin, a lawyer and amateur musician.

Domenico Maria Melli published his second book of songs in Venice in 1609. Among its contents was Se Di Farmi Morire?, for which Melli wrote both words and music in melodic and lyrical defiance of amorous rejection.

Pierre Guédron was sometime music director to Louis XIII of France, and is represented in the banquet by three ‘airs de cours’—verse-structured but relatively free-form solo songs for voice and optional accompaniment. The florid melody of Ce Penser Qui is found, like the two more we hear later, in Gabriel Bataille’s publication Airs de Differents Autheurs, Mis en Tablature de Luth. The chord-based accompaniment in the English style would have been added by a Dowland, probably John.

Lady if You So Spight Me by Dowland senior emphasizes the word ‘spight’ with an elaborately scored flourish, but the song is largely a breathless monologue which encapsulates the paradox at the heart of the text. Another of Guédron’s airs, Si Le Parler Et Le Silence warns repeatedly against placing trust in love courtesy of an adventurously disloyal vocal line.

Robert Hales was reportedly Queen Elizabeth I’s favorite singer. The simple basis of O Eyes, Leave Off Your Weeping would have given him a chance to show of his voice’s capacity for decoration and free expression.

The Dowlands were evidently taken with the excitable two-part rhythms associated with Spain, as heard in the anonymous dance Vuestros Ojos. O Dear Life returns us to Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella, another love song that prefers fraught questioning to idyllic repose. Dowland senior’s own A Dream meanders nonchalantly and nocturnally over the formal layout of a pavane—a slow processional dance that became widespread in Europe the century before—while Sta Notte Mi Sognava takes us further into night but with music far more florid than sleepy.

Dowland’s most famous song, In Darkness Let me Dwell, is an exquisite and quintessential work in which every one of the music’s longing discomforts come directly from the text, known from John Coprario’s collection Funeral Teares but itself anonymous. It was this piece, more than any other, that made A Musical Banquet such a celebrated publication.

Far From Triumphing Court is both a song of mourning for Queen Elizabeth I and an optimistic, even faintly heartening ode in welcome to the new queen, Anne of Denmark, daughter of Frederik II, who pays her future husband James I a visit en route to Copenhagen. The narrative text is by retired courtier Sir Henry Lee.

Vous Que Le Bonheur returns us to the art of Pierre Guédron, and a song whose bijoux suavity demonstrates all that was best about the French contribution to the lute song form.

Daniel Batchelor’s To Plead My Faith is a song in the form of a galliard. Its composer started out in Sir Robert Sidney’s court before becoming an official in Queen Elizabeth I’s Privy Chamber. The text is by the Earl of Essex, and implores incessantly across the song’s three sections, underneath which the lute’s inner voices sound increasingly agitated.

Giulio Caccini might have been a known quantity even to English audiences of the early 1600s, so widely distributed were his works including the 1602 publication La nuove musica. That is where the Roman composer’s Amarilli Mia Bella first appeared. Caccini is credited as one of the fathers of opera, and it’s certainly possible to hear the art form’s passions adumbrated in this work, a shining example of the ‘seconda prattica’ in which text took precedence over music (an ideal which supercharged opera’s rise). The Dowlands transferred the accompanying notation from that of ‘figured bass’—for continuo or keyboard instruments—to that of lute tablature (similar to today’s guitar notation).

So firmly did Caccini believe in the art of the solo singer, that his publication included a preface outlining the severe demands placed on anyone who deemed themselves capable of delivering any of his songs. Perhaps the ultimate test in that regard comes in the form of Dovrò Dunque Morire?, in which the singing actor is required to simulate death while singing—specifically, while singing the word ‘moro’ (‘I am dying’).

Notes by Andrew Mellor © 2022