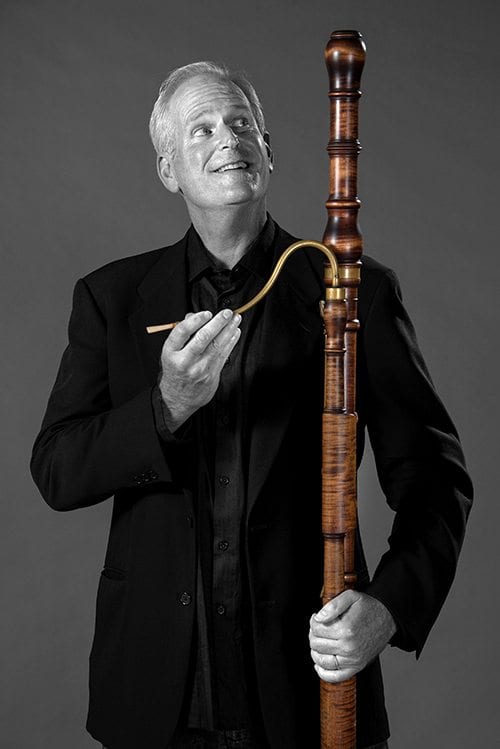

PBO bassoonist Andrew Schwartz with his replica bassoon by Guntram Wolf, Kronach, Germany, 2007; after Grenser.

NEW MUSIC FOR OLD INSTRUMENTS PART I

Woodwinds and Brass

Bruce Lamott

Although Jesus cautioned us that putting new wine into old wineskins is bad idea, his analogy doesn’t extend to writing new music for old instruments. While the musicians of Philharmonia do indeed play “old instruments” (also called “period,” or in early recordings, “authentic instruments”), the music they play is no longer confined to the period in which they were created. The technical mastery of these sometimes recalcitrant instruments has been achieved to such a point that musicians long to widen the horizons of their repertoire. PBOC is taking an active role in commissioning new works and introducing composers to the sonic potential of our Orchestra and Chorale through our New Music for Old Instruments initiative.

The Judas Passion by Sally Beamish, that opens our 2017/18 season, is one such work—a co-commission with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, the leading British period instrument orchestra. While the dramatic libretto by David Harsent retains some of the outward form of a Baroque opera or oratorio (recitatives, choruses, reflective solos), it is unencumbered by the strictures of ecclesiastical authority, as were the works of Handel and Bach. Jesus sings a new, non-Scriptural text, and the voice of God also sings the part of Devil. The eleven members of the Chorale, representing the disciples other than Judas, are not pious congregants but active participants in the drama.

Fifty years ago, period instruments were viewed by “establishment” orchestras and their audiences as a kind of Cro-Magnon stage in a Darwinian process of tonal and mechanical improvements; the fortepiano and viola da gamba, to name a few, were regarded as instruments that “died for a reason.” (To be fair, until they fell into the hands technically accomplished musicians who focused their attention on the mastery and pedagogy of these instruments, that opinion had some credence.)

PBO oboeist Marc Schachman with his oboe – a replica built by H.A. Vas Dias, Decatur, Georgia, 2001: after T. Stanesby, England, c. 1710.

If we listen to these instruments not as precursors of something familiar but as unique in their own right, what qualities make period instruments special? Two words: individuality and transparency. The woodwinds especially project their differences. The one-keyed transverse flute is gentle, with a sonic contour that rises from a soft lower range to a sensual and lyrical–but never shrill–upper range.

The baroque oboe does a lot of the heavy lifting. The penetrating quality created by a double reed is coated with a rich and colorful timbre (tone quality) that can be both plaintive and martial, even substituting for trumpets when the need arises. The oboes, when not playing lyrical or virtuosic solo parts, frequently double the violin parts in composite string/reed sound that is complemented by the bassoon doubling the cellos. The bassoon tone, like the oboe, is less nasal and richer in tone than its modern counterpart; I will even admit to having mistaken a baroque bassoon for an unusually sensitive tenor sax.

PBO trumpeter Kathryn Adduci with her trumpet: Rainer Egger, Basel, Switzerland, 2006; after L. Ehe, Nuremburg, Germany, 1748.

Baroque trumpets and horns can be both, well, brassy and melodious. Because of their association with martial and hunting topics, their use in baroque music is often stereotypical and somewhat infrequent. However, the sound of these instruments can be brilliant and commanding in the upper register, but lyrically vocal midrange. As with all of these instrumental colors, modern composers are no longer constrained by musical conventions and associations such as flutes and recorders with birds or trumpets with royalty.

The transparency of the composite sound of these highly individuated tone colors is one in which “blend” is not a priority. (Think of it as gazpacho vs. V-8 juice.) The clarity of the vibrato-less gut strings, rather than bathing the whole ensemble with a shimmering wash, allows the unique sounds of the winds and brass to permeate the texture, creating a kaleidoscopic interplay of timbres that open the door to a whole new sound world for modern composers.

PBO will present the U.S. Premiere of The Judas Passion by composer Sally Beamish, written expressly for period instruments, October 4-8, 2017. Learn more here.