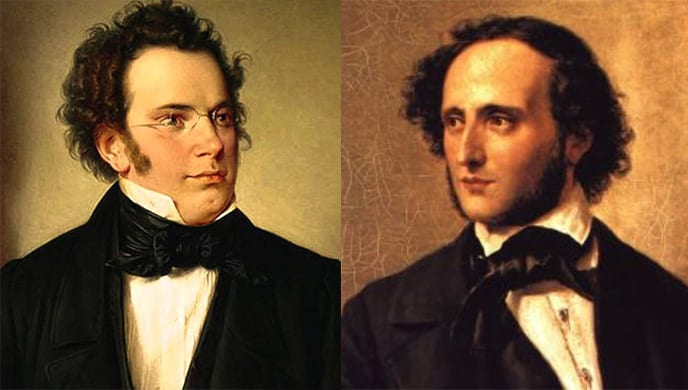

Schubert & Mendelssohn – A Tale of Two Prodigies

By Bruce Lamott

Franz Schubert by Wilhelm August Rieder, 1875

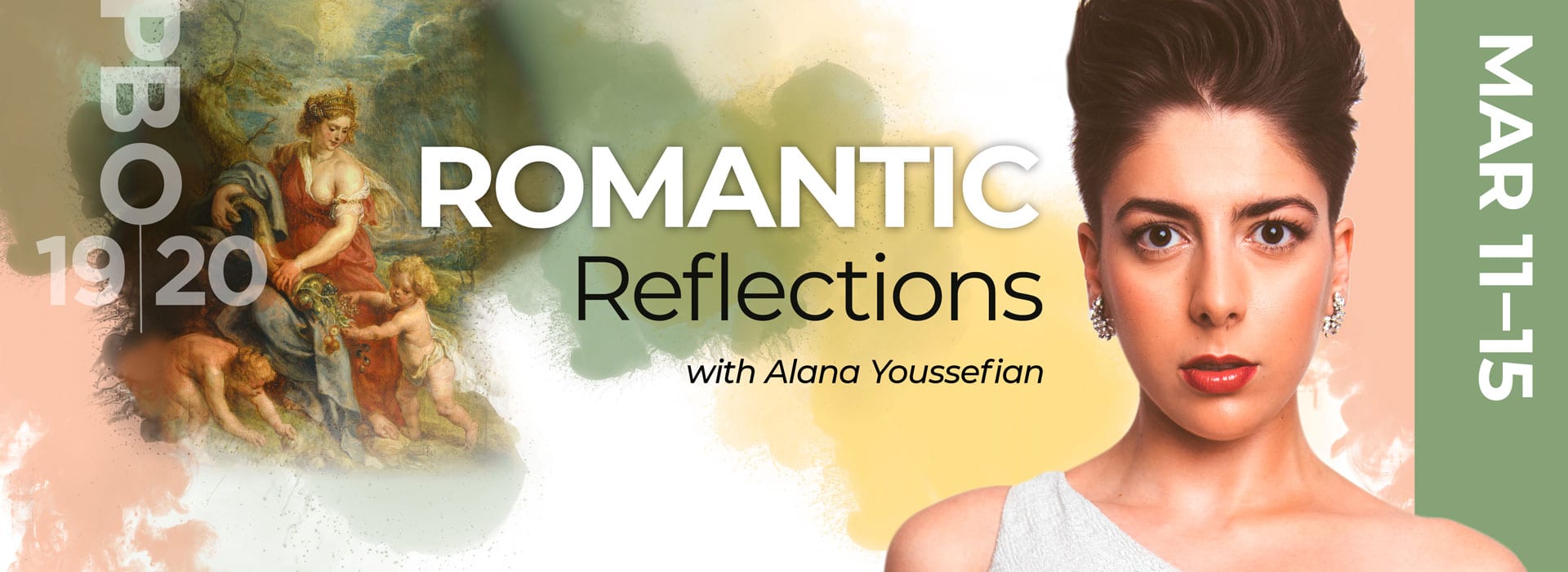

Nothing deflates a class of high school sophomores faster than telling them, after listening to Mendelssohn’s Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, that it was written by a fifteen-year-old. Or, enraptured by Schubert’s lied Erlkönig, they learn that he was seventeen when he had written it—along with over a hundred other songs, as well as string quartets, and a few symphonies (“Yeah, but they didn’t have to update their Instagram”). Both of the composers prominently featured in our upcoming “Romantic Reflections” program were recognized for their prodigious musical talents when very young, but striking differences in their social and economic circumstances led them down divergent career paths, the former to international celebrity and the latter, to relative obscurity.

Twelve years older than Mendelssohn, Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828) was the twelfth of fifteen children—nine of whom died in infancy—born to a suburban schoolmaster and his wife, a former housemaid, in a suburb of Vienna. From age eight, his father taught him violin and his elder brother piano, until their parish organist took over his tutelage; all agreed that his talents outstripped their skills. In a family string quartet, Franz played viola with his brothers Ferdinand (to whom we owe thanks for preserving the Great C Major Symphony on this program) and Ignaz on violin and their father on cello. At age eleven he received a scholarship as a choral singer to the Imperial Seminary (Stadtkonvikt), a tenuous position given the uncertainties of an unpredictably changing voice. There he got his first big break: he caught the attention of the celebrated composer Antonio Salieri (whose reputation was fictitiously maligned in the play and film Amadeus), who continued to give him lessons in music theory and composition until 1817.

By contrast, Mendelssohn was the second of four children born to a prominent Jewish banker, the son of the famed Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, and his wife, whose father upon converting to Christianity had adopted the name Bartholdy (when Felix’s family was baptized in the Reformed Church, they took the name Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, to further distance themselves from their Jewish roots). Felix’s sister Fanny was already an accomplished pianist and composer, and he grew up in Berlin in a cosmopolitan and intellectual household. After his mother’s early piano instruction, he was tutored in Paris, studied with a former student of Muzio Clementi, and by age ten was studying counterpoint and composition with Carl Friedrich Zelter.

Schubert’s poverty did not admit him to the rich cultural life of Vienna. However, as he played and occasionally conducted the orchestra at the seminary, he encountered the symphonies and other orchestral music of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, the German artsongs (Lieder) by Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg, in addition to the sacred music he sang in the seminary. After his mother died in 1812, Schubert lived at home with his father, and after teacher training, began teaching small children in his father’s school when he was seventeen.

Mendelssohn by James Warren Childe, 1839

By the time he was seventeen, Mendelssohn had been giving public performances for eight years, conducted private orchestra concerts at home, published a piano quartet, and written his magnificent string octet. He had met the elderly Goethe, studied with the virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles, and begun studies at the Humboldt University of Berlin. By the time he was twenty he had traveled to England and would later visit Vienna, Florence, Milan, Rome, and Naples. In 1829, his grandmother gave him a copy of a score of Bach’s then-obscure St. Matthew Passion, a version of which (reorchestrated and cut) he conducted at the Berlin Singakademie, launching the “Bach revival” and with it, a step towards the “historically informed” performance of earlier music.

Schubert’s subsistence led him back to his father’s school and home, and even in his brief adult life, most of his music was heard only in salons and private gatherings known as Schubertiades. In 1818, when he was twenty, Vienna heard the first public performance of any of his secular music, the Italian Overture. The furthest he ever got from Vienna was to the lake country of Upper Austria. And in 1839, eleven years after his death, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra first played his Great C Major Symphony, which Robert Schumann had discovered among his older brother Ferdinand Schubert’s scores. The conductor was the internationally acclaimed pianist, composer, and former child prodigy, Felix Mendelssohn.