BEYOND THE HALLELUJAH CHORUS

Bruce Lamott

Choral music occupies a major place in Handel’s works. For me and many others, his Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah was our first introduction to his music of any kind. My initiation came from the 300 voices of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singing on a Christmas LP you could get from the Firestone Tire store in Walla Walla, Washington, followed soon by the 15 voices of the volunteer choir at the First Presbyterian Church. To this day, Handel is sung by micro- and macro-choirs, amateur and professional, with period instruments and modern symphony orchestras. Since PBO aims to give “historically informed” performances with Baroque instruments, what historical information do we have about Handel’s choirs?

Choral music occupies a major place in Handel’s works. For me and many others, his Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah was our first introduction to his music of any kind. My initiation came from the 300 voices of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singing on a Christmas LP you could get from the Firestone Tire store in Walla Walla, Washington, followed soon by the 15 voices of the volunteer choir at the First Presbyterian Church. To this day, Handel is sung by micro- and macro-choirs, amateur and professional, with period instruments and modern symphony orchestras. Since PBO aims to give “historically informed” performances with Baroque instruments, what historical information do we have about Handel’s choirs?

The smallest “choral” ensemble is found at the end of many of his Italian operas, where coro simply indicated quartet or so of the principal characters–sometimes even dead ones who spring back to life in order to supply the bass line! Only a few operas require an independent choral ensemble, as stages were small and budgets were tight.

The Chapel Royal, Greenwich

But in his oratorios, Messiah for example, Handel wrote for what we think of as a real choir, though not what we might expect. His oratorio choristers were drawn from the churches of London as well as the Chapel Royal, and since women could not sing in those choirs–thanks to the Anglicans’ literal adherence to St. Paul’s admonition that “women should be silent in church” [1 Cor. 14:34]–they were choirs of men and boys. Only the solo roles were sung by women. The choral soprano parts were sung by trebles (boys with unchanged voices), the altos were adult men (fully intact, not castratos) called countertenors, singing in falsetto, along with tenors and basses. Since the onset of puberty was much later for both sexes in this period, Handel’s trebles could have been as old as eighteen.

For a sampling of Messiah sung by such an ensemble, in costume, check out this video.

Even the all-male choir did not satisfy the misgivings of some noted clergy, however. When Handel premiered Messiah in Dublin, he asked for singers from Christ Church and St. Patrick’s Cathedrals. But finding that they were to perform the Word of God in a music-hall and not a church, St. Patrick’s Dean Jonathan Swift sent out a memo threatening to punish anyone who should perform in “a club of Fidlers [sic] in Fishamble Street,” concluding, “My Resolution is to preserve the Dignity of my Station and the Honour of my Chapter.”

Even the all-male choir did not satisfy the misgivings of some noted clergy, however. When Handel premiered Messiah in Dublin, he asked for singers from Christ Church and St. Patrick’s Cathedrals. But finding that they were to perform the Word of God in a music-hall and not a church, St. Patrick’s Dean Jonathan Swift sent out a memo threatening to punish anyone who should perform in “a club of Fidlers [sic] in Fishamble Street,” concluding, “My Resolution is to preserve the Dignity of my Station and the Honour of my Chapter.”

But Messiah‘s famed choruses lead us astray in considering the choruses in Handel’s Joshua or nearly all of his other 25 oratorios. In these the choir plays a dramatic role–sometimes more than one, in these works, not singing the words of Scripture but texts written by a poet, the librettist. At times, the chorus plays opposing roles such as the wanton Babylonians and righteous Israelites in Belshazzar. In Joshua, our Chorale will sing the single role of the Israelite people, whose texts are both Biblical paraphrases and creative dialogue written by Rev. Thomas Morell. These Israelites exult when they arrive in the Promised Land, narrate vividly in describing the fall of Jericho, and suffer in defeat as they retreat from the siege of Ai.

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, 2014.

The 24 professional singers in the Philharmonia Chorale, while more diverse in gender than Handel’s choir, number about the same. Each singer is selected not only for vocal quality but for expression and presence, in order to project a range of emotion that connects individually as well as collectively with our audience.

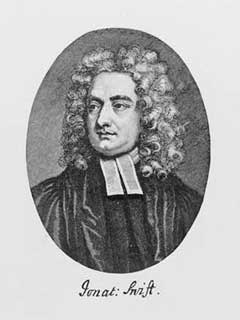

See Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale perform Handel’s Joshua December 1-4 throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. Get tickets on the button below.