Virtuosity on Ice

By Bruce Lamott

Mirai Nagasu becoming first U.S. athlete to land a triple axel at the Olympics, 2018. (Photo courtesy World News.)

It may be a stretch to suggest that audiences watching the Winter Olympics or PBO’s upcoming set, “Corelli the Godfather,” are looking for the same thing, but it’s undeniable that a Corelli concerto and a perfectly executed figure-skating routine both captivate their viewers with the same ephemeral quality: “virtuosity.” Though the term’s original derivation from the Latin virtuosus meant “learned” or “skilled,” modern usage of “virtuosity” implies conspicuous demonstration of skill, whether shown in a triple-axel, a brilliant violin solo, or a gravity-defying Bernini sculpture.

It’s not surprising that the Italian term virtuoso first appears in 17th century Italy, right along with the style period now known as the Baroque. This was an era in which works were created that challenged the techniques of singers and instrumentalists to play faster, higher, and with more overt emotion than ever before. [NB. Though the original English term for such a performance was virtuous, the moral character of many decidedly un-virtuous virtuosos quite possibly led to the alternative adjectival form of virtuosic.] To be sure, virtuosic riffs are found in Renaissance treatises for recorder (Ganassi) and viols (Ortiz), but these were DIY manuals for improvisers. Keyboard variations by the English virginalists (harpsichordists) such as William Byrd were written-down examples of the kind of extemporaneous improvisations expected of any well-trained keyboard player.

Arcangelo Corelli (portrait by Hugh Howard, 1697)

Baroque virtuosity, on the other hand, was obligatory, clearly demanded by the score itself or–in the case of slow movements and cadenzas–implied by performance practices. The concerto grosso, a genre which figures prominently in our March program, was developed by Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) and his followers. It was a splendid vehicle for juxtaposing virtuosic passages of a small solo group (called the concertino) with a unified response from the whole ensemble (the ripieno, or tutti). Virtuosity in these works is found in two kinds: the impressive double-lutz bowing and fleet fingerwork of the fast movements and the filigree of riffs which are improvised around the simple melodies and slow-moving harmonies in the slow movements.

Corelli and his followers were constantly pressing the envelope of violin technique, and tricks of the trade resulted in “schools” centered on the pedagogy of a particular Italian master, for example, Tartini in Padua, or Corelli in Rome. Corelli’s disciples set out in mass migration throughout Northern Europe, and a clique of English gentlemen on the Grand Tour sought out Corelli for social and musical bragging rights. ‘Corelli-mania’ swept through France and England, greatly influencing the work of George Frideric Handel, who had known Corelli personally during his youthful years in Italy.

The inclusion on our program of one of Handel’s organ concertos featuring conductor Richard Egarr is also a nod towards virtuosity and showmanship. Handel advertised these works as intermission features between the acts of his sacred oratorios, and despite rude commentaries about the corpulent composer (“with fingers as fat as toes”) negotiating his own virtuosic passages, he was nonetheless good for the box-office. Like Handel, Mr. Egarr will improvise two of the movements of his concerto which the composer indicated were to be played ad libitum, a feat which reflects the original twofold definition of the virtuoso: skilled and learned.

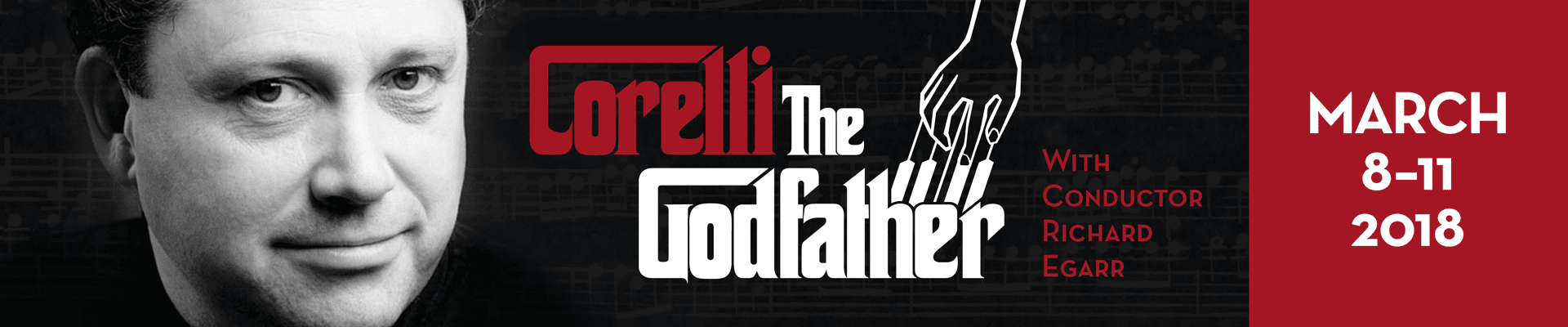

See PBO’s virtuosity on display in a program of concerti grossi led by keyboard master Richard Egarr who is planning a perfect landing on Handel’s Organ Concerto No. 15 in D minor. Concerts in San Francisco, Berkeley and Standford March 7-11, 2018. Learn more and get tickets.